MISSINGPERSONS: LaTonya Moore poses with her daughter’s urn, Shantieya Smith, inside her home 150 miles away from Chicago. May 11th, 2023. Smith was reported missing and later found murdered near her home in North Lawndale in 2019. Her cases was among the 99.9% percent of missing person cases of Black women and girls between 2000 and 2022 the Chicago Police Department labeled cold or showed noncriminal. Smith lives through her only daughter and mother, LaTonya Moore, both struggle with grief over the unanswered questions. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo for City Bureau

By

This story is part seven of Chicago Missing Persons, a two-year investigation by City Bureau and Invisible Institute, two Chicago-based nonprofit journalism organizations, into how Chicago police handle missing person cases reveals the disproportionate impact on Black women and girls, how police have mistreated family members or delayed cases, and how poor police data is making the problem harder to solve.

Why do people go missing in Chicago? Missingness is embedded in social conditions such as gun violence, intimate partner abuse, inadequate housing, and lack of safe space for teens — issues related to structural racism that city officials perpetually struggle to solve.

City Bureau and the Invisible Institute’s two-year investigation into how Chicago police handle missing person cases reveals the disproportionate impact on Black women and girls, how police have mistreated family members or delayed cases, and how poor police data is making the problem harder to solve.

City Bureau and the Invisible Institute’s two-year investigation into how Chicago police handle missing person cases reveals the disproportionate impact on Black women and girls, how police have mistreated family members or delayed cases, and how poor police data is making the problem harder to solve.

It also shows how, for Black Chicagoans, the trauma of having someone go missing is compounded by having to fight for adequate police services and having to defend against victim blaming. Life often goes on without the promise of resolution or public recognition of their loss — a loss that Black families describe as ambiguous and unending, unacknowledged in media and police narratives.

“Just because of the color of your skin, we shouldn’t be treated any differently. But that’s what this world is all about,” says Shirley Enoch-Hill, the mother of Sonya Rouse, a Black woman who disappeared from her Chatham home in 2016 and whose case remains unsolved.

City Bureau and the Invisible Institute spoke with dozens of Black Chicagoans in an effort to understand what it means to have a friend, sister, or daughter go missing. Here are some of those stories.

SHANTIEYA SMITH

(See more of Smith’s story in Parts 1 through 6.)

Neighborhood: North Lawndale

Last seen: 2018

Age last seen: 26

Located: Yes. Died by homicide.

Years have passed. The abandoned garage where Shantieya Smith was found is torn down, and some neighbors still avoid the alley entirely. But in some ways, it feels like people have forgotten Smith, says her mother, Latonya Moore — the phone calls and visits are fewer and fewer, the likes on her social media posts almost nonexistent.

Moore is raising Smith’s now-12-year-old daughter in rural Illinois near the Iowa border, 140 miles from the city of her birth and her community. After she lost Smith, behind on her rent and close to an eviction, Moore felt there was one choice: to leave the city that failed her.

Today, she juggles her granddaughter’s schooling and keeps a watchful eye over who the pre-teen speaks to online, which friends she surrounds herself with, and how she copes with her mother’s death.

Sitting at the local diner this April, shoulders touching with her grandmother, the teenager taps and slides her fingers across her phone screen playing a video game with headphones on as Moore describes how Smith’s death has impacted both of them.

“She doesn’t call me grandma,” Moore says. “She says I’m her mom because she doesn’t want kids at school to know that her mom is deceased.”

While she shoulders her own grief, Moore tries her best to emulate the type of love that Smith poured into every birthday celebration, school assembly and report card, and the steadiness of their early morning strolls to school. “She wanted her daughter to be something someday,” Moore says of Smith.

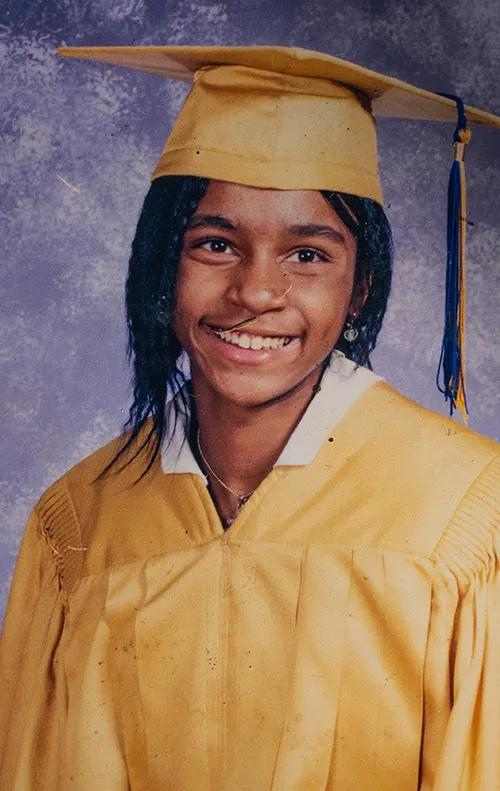

Shantieya Smith’s high school graduation photograph, which her mother Latonya Moore displays prominently in her living room. (Photo: Sebastián Hidalgo)

Later that month, Moore received an unexpected phone call from a West Side pastor who had helped her in the worst moments of her daughter’s missingness. Would she be willing to sit on the state’s first task force on missing and murdered women to speak truth to the issues that stole her daughter’s young life?

Her initial surprise at the invitation to sit among the state’s top law enforcement brass and policymakers soon tumbled into contemplation. Could the Chicago Police Department really reckon with how it handles missings persons cases, the bias and stereotypes? Moore wondered what it would be like to finally tell police, face to face, the concerns she collected over the years. Mostly, she wanted top brass to acknowledge the racism that impacted how they handled her daughter’s case, and to explain why they blamed Smith herself instead of finding who killed her.

“They need to stop thinking that everyone is into prostitution and drugs,” she says. “You don’t know someone’s story.”

In the end, she declined to join. Moore says the task force won’t bring Smith back, even though she recognizes that the solutions need to center survivors, such as herself. Moore plans to find other ways to keep Smith’s name and story alive and find justice for her daughter. She prays it’s a battle that will end before Smith’s daughter becomes a woman.

“I’m grieving, but I’m looking for closure. If I get closure, then I could rest,” she explains. “If it don’t ever rest, then I’ll take it to my grave.”

SHANTE BOHANAN

Neighborhood: Marquette Park

Last seen: 2016

Age last seen: 20

Located: Yes. Died by undetermined cause.

Shante Bohanan was at a crossroads.

In the summer of 2016, the 20-year-old got a new job at a South Side Taco Bell and was enjoying a newfound confidence in herself. “She finally felt like an adult, accomplished,” her older sister, Tabitha Pittman, remembers.

For Bohanan’s family, there was a particular sweetness in watching her bloom. After her parents separated and she lost a cousin to gun violence, she moved from the West Side to the South Side and struggled finding the right friends, Pittman says. Now she was getting a fresh start.

Tabitha Pittman was incredibly close with her sister Shante Bohanan, who had recently moved from the West Side to the South Side in 2016. (Photo: Natasha Moustache)

“I look back on it, and I say it made me happy because I could finally see the woman she was going to become,” says Pittman. “I knew that it was going to be something beautiful.”

Bohanan was the baby of the tight-knit West Side family that often traveled together to visit family in Mississippi and Tennessee. She was a social chameleon who was as comfortable kicking it with people her age as she was playing a round of spades with her mom’s friends. When she was a child, an uncle called her “little old folks.”

“She was very outspoken, outgoing, very friendly and had a lot of friends,” says Tammy Pittman, Shante’s mother. Although Bohanan was skinny, about 100 pounds, “if you let her tell it,” her mother recalls with a laugh, she would say, “’I have booty. Look at my booty, Ma.’”

A few weeks before she went missing and was found dead in an abandoned garage in July 2016, Bohanan had started dating a young man. Her mother only remembers meeting him once before tragedy hit. While they were walking together, her boyfriend was shot and killed. Bohanan later recounted to her family how she ran for her life as bullets hissed around her. A nearby store owner recognized she was in danger and let her hide in his bathroom until her mom came to get her.

“She was terrified,” her mother remembers. “She kept saying, ‘He’s dead, he’s dead.’”

Rumors spread on social media that Bohanan had something to do with her boyfriend’s murder “because she didn’t get hit,” her sister says. Bohanan “didn’t know if it was safe for her to go to certain neighborhoods or talk to certain people,” she adds.

So her mom and sisters did what families do: They circled around Bohanan to protect her. Together, they built their own safe house at Tabitha Pittman’s red brick two-flat in North Lawndale — three sisters and their mother in one bed. “There is no such thing as me telling my sisters that they can’t stay in my bed. It was her, my mom, and my other sister, and they were all in my home, cuddled up,” Bohanan’s sister remembers with a laugh. It was one of her last memories of her little sister.

Her mother remembers packing up for church one Sunday morning, hoping that Bohanan would come with her, but she declined — she didn’t feel well. Instead, she planned to go to her boyfriend’s family’s house to grieve. Though Tammy Pittman urged her to stay away for her own safety, Bohanan felt the need to pay her condolences. It would be the last moment that Pittman saw her daughter alive.

Later that day, Bohanan called one of her sisters to say that she had a “gun held to her head” and was not allowed to leave the boyfriend’s family’s house, an incident documented in police reports. Frantic, her family members mobilized to find her, but when they went to the boyfriend’s house, the residents said that Bohanan had already left. Tammy Pittman immediately went to the police station to ask officers to search the house, but officers suggested that Bohanan had run away, she says. They urged her to wait another 24 hours before reporting her daughter missing, against state law and police policy. Pittman remembers she brought Bohanan’s dad to the station with her the next day to insist that the officers accept the missing person report, which they did.

Tammy Pittman says it wasn’t until the night after she first contacted police that officers finally searched the home where she suspected Bohanan was being held, and found nothing. Two days later, her daughter’s body was found naked in a garbage bag in a garage on 92nd Street in Burnside. The cause of death is “undetermined,” according to the medical examiner’s office.

Shante Bohanan’s memory lives on through her sister Tabitha Pittman’s boutique. Pittman hopes the space can empower young women. (Video credits)

After Bohanan’s death, her older sister decided to open a clothing boutique in Lansing, Illinois. Before then, Tabitha Pittman had designed and sold clothes online. “When my sister was murdered, I decided to open up a safe location where anybody could come in and feel confident and just be able to create themselves as well,” she says, hoping that young women like Bohanan could find safety and a friendly face there. She named it Shante Nicole’s Boutique, “so her story won’t be forgotten,” Tabitha Pittman says.

She remembers one prom dress commission the year after her sister’s death. A teenage girl wanted a red gown with a dramatic slit up the thigh — a look and color that Bohanan would have loved. The dress was a labor of love to maintain, in some quiet way, the memory of her sister. As she touched the red silk and hand stitched on sequins, Pittman felt closer to Bohanan, putting in the same care she would have for her little sister’s dress.

When you lose a child, your whole world changes. Even though her mother is in a new apartment now, Bohanan is everywhere. “I could be cooking, and I know what kind of foods she liked,” she says. “I hear her say, ‘You know I don’t want no BBQ sauce on that,’ or I could be fixing my rice in the morning, and she’ll say, ‘Give me that, Ma. I want my rice just like how you fixed your rice.’” Sometimes, Tammy Pittman will see Bohanan’s magnetic smile move in photos of her, as if her spirit, too, cannot let go.

Tammy Pittman says she hasn’t heard from detectives in five years. If the police had acted more urgently, she wonders, would Bohanan still be alive?

SONYA ROUSE

Neighborhood: Greater Grand Crossing

Last seen: 2016

Age last seen: 50

Located: No. Still missing.

In the mid-1990s, Sonya and Bridgette Rouse would hit the clubs. “It was a ‘Sex in the City’ sitcom — two Black sisters, just running around, doing our thing in Chicago,” says Bridgette Rouse.

Rouse would watch in admiration every time her older sister, Sonya, went under the bright lights of the Cotton Club and drew people to the empty dance floor.

“Sonya didn’t really care whose eyes were on her,” she remembers. “It was just her way of connecting socially, not with other people, but with herself.” Music was a form of treatment for her older sister’s depression because she found peace in rhythm.

Shirley Enoch-Hill says her daughter Sonya Rouse was a bookworm who loved to dress in bold and bright colors. Here, Enoch-Hill sits with Rouse’s granddaughter and a portrait of Rouse. (Photo: Natasha Moustache)

Sonya Rouse, who went missing in March 2016 at the age of 50, was the older sister you could talk to about anything, her sister says. She was a contradiction, at times: the life of the party but also quiet, reserved until she knew you, but with a bold and bright style that spoke for her when she walked into a room.

“She loved to dress,” her mother, Shirley Enoch-Hill, remembers of the oldest of her three girls as she sits near a colorful painting of Sonya that hangs in the family room of her Lynwood, Illinois, home.

That was Sonya: clever and funny but also sensitive and shy. As a child, she was the bookworm in the family, often holed up in her room reading the newest book she’d received from her children’s book club. “She just loved to read and that’s all she did,” says Enoch-Hill.

After graduating from Kenwood Academy, Sonya Rouse headed downstate to Illinois State University, where she studied communications and journalism. She dreamed of being a journalist, maybe even the next Oprah Winfrey, her mother remembers. She was the first in her family to graduate from college.

To this day Enoch-Hill wonders if her oldest daughter is still alive.

Things changed after Rouse moved back to Chicago from college in the early ’90s and gave birth to a daughter. After the birth, Enoch-Hill recalls, postpartum depression gripped Rouse. Substance use and untreated mental health conditions drove her into a cycle that the family was unsure she would survive.

“I remember one doctor said, ‘Sonya, if you would just let me help you with the medication and stop trying to self-medicate yourself, things would be better for you.’ I would say, ‘You can do it, you’re strong.’ And she said, ‘No, mother, you’re strong. I’m not as strong as you are,’” remembers Enoch-Hill. Eventually, she raised her granddaughter because Rouse “couldn’t get herself together.”

“The depression just got the best of her,” says Enoch-Hill.

Rouse met a boyfriend in rehab and got clean for a while, but the relationship ended when she relapsed. It got so bad that her mother set up a safety plan: She would check in every few days over text or a phone call, and if she didn’t hear back, she would report Rouse as missing to the Chicago Police Department. Enoch-Hill knew that her daughter’s health issues put her at risk of going missing or being the victim of a crime.

Rouse then started seeing a man and moved in with him at a house in Greater Grand Crossing. He physically abused her, Enoch-Hill says. She would run from him, and sometimes the police or her family would come to get her out of the house.

“It hurts you to see your child being abused, beaten like that. It seems like they’re listening, but when they go back, it’s like the abuser has the upper hand,” says Enoch-Hill. “I went and got her several times … but she kept going back.” That’s how she knew something was wrong — too many days had passed without their regular calls and text messages.

In March 2016, on a rainy Sunday after church, Enoch-Hill knocked on the door of Rouse’s home where she lived with her boyfriend. Earlier, she had received a text message that didn’t feel like it came from her daughter. No one answered the door, and she never saw her daughter again.

After filing a missing person report, Enoch-Hill says family, friends, and church members did everything they could to locate Rouse. They posted flyers in her neighborhood and held prayer vigils outside her house. Enoch-Hill talked to her neighbors. They sent tips to her detective, urging him to interview Rouse’s boyfriend and search her home.

Media attention was scant and sterile. “Rouse is diagnosed with bipolar disorder and has emotional issues. She could be carrying a purse,” one news report said.

Bridgette Rouse wrote letters to then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel, news outlets, and the Chicago Police Department. She constantly called the Special Victims Unit and pressed Detective Brian Yaverski, assigned to the case, for updates on the investigation.

The younger Rouse sister remembers one interaction with Yaverski that she can’t shake.

“He stated that my sister’s struggle with alcoholism and her mental health led her to illicit behaviors. I responded saying, ‘Does that mean you shouldn’t be searching for her?’” recalls Bridgette Rouse, who felt Yaverski blamed her sister for her own disappearance.

Enoch-Hill feels that the police didn’t take her daughter’s case seriously because she was a missing Black woman, and she warns others that it could happen to them. “Hold on to your children, talk to them, try to get them some help because if they come up missing, it’s like nobody cares,” she says. “The police don’t care — that’s how I feel.”

According to police documents, the boyfriend was in a work release program through the Illinois Department of Corrections when Yaverski attempted to interview him. An IDOC official said they could accommodate an interview by bringing the boyfriend back into custody, but Yaverski stated that he would wait until the boyfriend was fully released. Medical examiner data shows that he died of fentanyl overdose in December 2018, and there’s no indication in police records that he was ever interviewed in relation to Rouse’s case. Yaverski did not respond to a request for comment from City Bureau and the Invisible Institute.

Enoch-Hill feels that if the detective had interviewed Sonya Rouse’s boyfriend, he might have discovered what had happened. “When he died, the truth of what happened to Sonya did as well,” she says.

Enoch-Hill believes that if her daughter had been a white woman on the North Side, the detective would have handled the investigation differently, “but because she’s Black, and from the South Side, nobody is trying to find her. That’s how [police] made you feel.”

Looking back, Enoch-Hill sees a pattern amid her daughter’s inability to break free from an abusive relationship and her struggle with mental illness, substance use, and her eventual disappearance. “She told me, ‘Mother, it’s the demons that I’m running from; there are things I can’t face.’”

No parent wants to lose a child, but it’s a singular sort of pain when “you don’t know where your child is on this earth,” Enoch-Hill says.

“It’s a strange and sad situation when you can’t put your children to rest,” says Enoch-Hill, who adds that she is not going to give up hope.

“There’s no closure.”

TAKAYLAH TRIBITT

Neighborhood: Noble Square

Last seen: 2019

Age last seen: 14

Located: Yes. Died by homicide

Takaylah Tribitt was known as Lady Bug.

Small and energetic, the fifth-grader hit it off immediately with the girls who would become her best friends when she transferred to John B. Drake Elementary next to the Dearborn Homes public housing development in 2015.

“Ever since that day, I knew we would be close,” says Tamia Scott, who is now 18 years old. Over the years, Scott recalls, Tribitt was always the most intelligent girl in the room — the one whose homework they’d all hoped to copy, whose bright smile was like a lightbulb.

Although she didn’t have her own phone, Tribitt was always laughing, dancing in a TikTok “before it was popular,” or taking a selfie on Snapchat in junior high, Scott recalls.

Tamia Scott remembers her friend Takaylah Tribitt, a smart teen who was always laughing and dancing, she says. (Photo: Natasha Moustache)

In seventh grade it became apparent to her friends that behind her smiles, Tribitt was struggling with an unstable home situation as well as being diagnosed with bipolar disorder. “The only clothes that Takaylah had were the clothes that she had on,” says Scott.

Her friends saw marks on her face and body, and she told them she was experiencing abuse. When kids found out she ran away from home frequently, she was bullied at school, says Jada Nile, another friend of Tribitt’s who is now 18. They would try to protect her by hiding her in their homes or running away with her themselves to swim, eat food or sleep at a grandma’s house.

But they would always get caught. Soon their parents urged them not to let their friend stay over, fearing the police would come looking for her.

Toward the end of her short life, they noticed small things like her nails being done or a box of pizza and wings she’d shared with them. It didn’t add up.

“We kept asking her, where did you get it from? And she kept saying, ‘Oh, I have my ways,’” says Scott. “Nobody knew what Takaylah was doing.”

Nile saw a final message from Tribitt pop up on her phone after a disagreement they had that summer: “I’m sorry.” She needed space and didn’t text back.

A Night Ministry temporary youth shelter employee reported Tribitt missing to the Chicago Police Department on Sept. 2, 2019. She had run away 10 times that year, according to a police case file.

A shelter resident told investigators that Tribitt wanted to leave and went through the back gate of the facility. Less than 24 hours later, she met up with an older man who started beating her, a case file recounts. She messaged a friend from the man’s house to ask for the youth shelter’s address or a ride back, but abruptly hung up when he came home.

Deonlashawn Simmons, who was in his early 30s, had been corresponding with Tribitt on Facebook Messenger, according to a police report. She hid it from her closest friends because she knew they wouldn’t have wanted her to put herself in danger, Nile and Scott say.

“She was just trying to survive, to have food to eat,” says Nile. “If she didn’t have nowhere to sleep, she was able to sleep at his house. He was buying her food, taking her out, buying her hair [extensions].”

Despite being a 14-year-old girl coping with mental illness who could have been classified as a high-risk missing person, which would require immediate action according to Chicago Police policy, a detective was not assigned to her case until Sept. 7, six days after she was first reported missing. A detective finally interviewed the person who reported her missing Sept. 11, according to her case file.

To this day, Nile and Scott still think about what they could have done to save their friend’s life. “I wish she had an adult that understood her,” says Nile.

Now as 18-year-olds, they understand that Tribitt found a home and a refuge with her friends. A community circled around her the best it could during junior high. Security guards at a friend’s building gave her a big bag of Jordans and clothes, and a stylist would braid Tribitt’s hair for free. But without the stability she needed, Tribitt was forced to find other ways to survive.

“She needed somebody to actually motivate her, not just 14-year-old kids,” says Scott. “She needed more guidance from an adult that would stick on her and tell her what is really the right thing and what is not.

“I blame everybody, and I even blame myself,” Scott says. “I be angry now, still even trying to think to myself … What did I do wrong for her not to tell me?”

But then she remembers how hard it was at that age not to bottle everything up and hide the hard parts of life out of shame.

Takaylah Tribitt and her friends were like family to each other. After she went missing at the age of 14 and was found murdered, her friends still cope with grief. (Video credits)

“We were overprotective, and we didn’t want her to do certain things because of her safety, and we knew she could make mistakes, and we didn’t want the mistakes to be bad,” says Nile.

Five days after she shared pizza and wings with her friends at the Dearborn Homes, Tribitt was found dead, face down with her hands tied behind her back and a cord around her neck, in an alleyway strewn with trash and overgrown vegetation in Gary, Indiana, according to a Lake County (Indiana) Sheriff’s report. A single spent bullet casing lay near her waist. One neighbor told Gary investigators she wasn’t surprised someone found a body in a neglected area known for sex work. Tribitt was a teenage Jane Doe.

On Oct. 10, investigators matched Tribitt’s DNA to her mother’s and identified her.

Police documents say that Simmons had taken her across state lines and murdered her. Investigators suspected that Simmons was sex trafficking Tribitt, though he was never charged with this crime. A Lake County judge sentenced Simmons to 105 years for her murder in 2022.

That’s a small comfort to her friends. “He took her away from her people forever,” says Nile. “You can’t get her back.”

Tribitt’s boisterous laugh, the one that had driven Nile crazy all those times before, the one that was distinctively hers, comforts Nile when she thinks of her best friend.

“She was my little big sister. She was older than me. It’s crazy that my age passed hers. It wasn’t supposed to be that way,” says Scott. “She was supposed to be in high school. She was supposed to live her life.”

Tribitt’s murder is a loss that continues to reverberate in the lives of her friends — a pain and a grief that holds them together.

“I lost her in the worst way possible. I still grieve for her to this day,” says Scott. “The only way I can grieve is with myself or her other best friends that know the feeling of losing her.”

Last fall, Tribitt’s friends gathered to slice a pink and white cake in celebration of what would have been her 18th birthday. The memory of their best friend brought them together to celebrate another birthday she missed, her name forever etched across their forearms and chests in black cursive tattoos: Takaylah.

This story is part of the Chicago Missing Persons project by City Bureau and Invisible Institute, two Chicago-based nonprofit journalism organizations. Read the full investigation and see resources for families at chicagomissingpersons.com

This story was also published in Word in Black.