After a tragic drowning during Chicago’s Black Yacht Weekend, longtime boater Aven Deese shares a sobering eyewitness account—and what must change to keep the Black boating community safe on Lake Michigan (Photo Provided).

When Black Yacht Weekend came to Chicago two weeks ago, the fervor was palpable. The fact that it occurred around Juneteenth was symbolic, as it was billed as a celebration of Black culture, community and luxury—a declaration that Chicago’s Black boating community, vibrant and expansive, has staked its claim along the shores of Lake Michigan, in a realm long dominated by “rich white guys.”

Yet during—and after—the self-proclaimed largest floating festival for Black boat enthusiasts in the country, troubling reports surfaced: overloaded vessels, passengers tumbling overboard, intoxication everywhere. The weekend took a grim turn when a 27-year-old woman drowned in the Playpen, the crowded anchorage just north of Navy Pier. (Organizers issued a since-deleted Instagram statement expressing sympathy while noting the incident “did not take place within the Black Yacht Weekend event area and has not been officially linked to any of our attendees.”)

Still, one veteran boater summed up the chatter rippling through harbors from Jackson Park to 31st Street. “Deaths. People falling over in the water. It’s a mess,” the longtime captain texted The Defender.

To separate rumor from reality, The Defender spoke at length with Aven Deese, a 45-year-old CPS educator, summer fishing instructor and lifelong boater. Deese has logged enough hours on Lake Michigan to know when fun tips into recklessness. What follows is an edited look at his on-the-water eyewitness account—and what might come next for Chicago’s Black boating movement.

‘A boat is not a nightclub’

A photo from a previous Black Yacht Weekend (Photo Courtesy of blackyachtweekend.com).

“The first thing that came to mind was safety,” Deese began. “A boat is not a nightclub. It’s a boat.” He described a Playpen packed with party craft, many operating as unlicensed charters.

“I saw a lot of unsafe behavior both in the Playpen, and from the Playpen,” he said. “People have the idea that, ‘We’re going to get on this boat, we’re going to get really drunk and have a great time.’ That is not the mindset you want to have.”

Drugs and alcohol, he added, can turn Lake Michigan’s deceptively calm surface lethal in seconds: “You are stepping onto a body of water that can take you really quickly… You can lose your life, as we saw that weekend.”

Lake Michigan: A ‘Small Ocean’

Deese warned that many newcomers and out-of-towners underestimate the lake. “I don’t care if you can’t swim or if you’re Michael Phelps—the lake itself is not what we think of as a lake.”

He points out currents that drag fishing lines sideways, water often stuck in the mid-60s even in July, where swimmers can risk hypothermia or worse, depths of 700-plus feet. All of it conspires against overconfident swimmers—or nonswimmers who refuse life jackets.

“At the end of the day, you’re dealing with a body of water that is, for lack of a better term, a small ocean,” he said. “You need to respect it as such, because if you go into that water— between the cold and the currents—you are going to be fighting for your life. Usually, you don’t win.

Cheaper boats, costly upkeep

Social media can glamorize boat life and the relative affordability of watercraft, especially on sites like Facebook Marketplace, can fool unsuspecting buyers, who can get swamped with high maintenance and docking fees.

“You can get a 30-, 40-, sometimes 50-foot boat for less than the price of a brand-new Honda Civic,” he said. Dockage alone can hit $7,000 a summer. Winter storage and repairs pile on; diesel fill-ups run hundreds per trip.

Then there is the matter of getting the right training to properly navigate your watercraft, something that novices often skip entirely. Deese said the Coast Guard offers an eight-week course and notes that a proper captain’s license demands 360 days on the water, plus drug tests and physicals.

However, many weekend operators skip those requirements, Deese said, pushing overloaded rentals to maximize profit and ultimately putting their passengers’ lives at risk.

Pressure to launch, even in gale-force gusts

Because customer reviews rule booking sites, captains feel trapped.

“No one wants to be the guy that constantly cancels,” Deese explained. Some cave to passengers who traveled for the festival, steering into 15-mph winds and four-foot waves. “They just want their experience, come hell or high water, and unfortunately, some people pay with their lives.”

Overloading: where disaster begins

Overcrowding was rampant during Black Yacht Weekend, said Deese. A 25-foot pleasure craft safely fits eight people, maybe ten in a pinch. On the waterways, he counted 15 or more on boats—enough to swamp the stern.

“A lot of those guys don’t know how to say no,” he said. The result: half-submerged transoms due to overloading.

A cultural collision on the water

The Playpen has long been a playground for affluent white men. Still, Deese observed, seeing Black crews drop anchor there and at other harbors has rattled some and fueled stereotypes when mishaps occur.

“We have a lot of bad actors who are not doing what they’re supposed to do… When these events happen… [the] majority group says, ‘Welp, there they go again.’”

However, the Playpen has had recent issues with bad actors engaging in unsafe and illicit activities while aboard watercraft.

“People have been falling off, dying and harming themselves in the Playpen far before Black folks showed up,” Deese said.

After Black Yacht Weekend, he predicts stepped-up policing at predominantly Black harbors—31st Street and 67th Street—as federal and state agencies scramble to curb “the shenanigans.”

How to board—safely

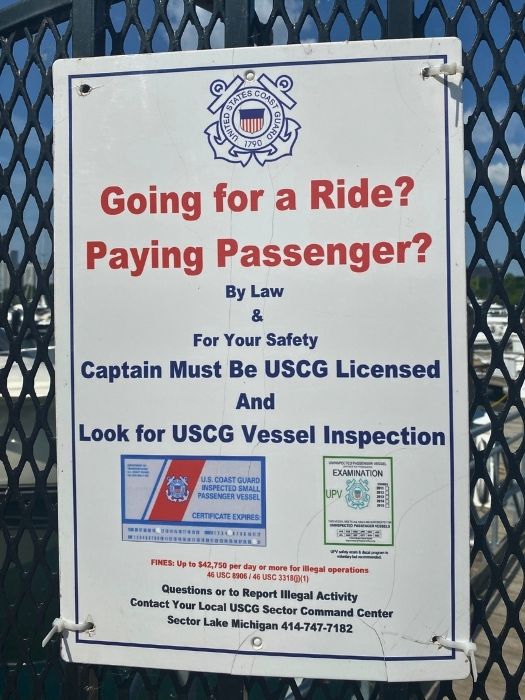

Coast Guard safety signage at a Lake Michigan boating dock (Photo Credit: Aven Deese).

Deese’s advice to future passengers and organizers is blunt:

- Book legal charters only. Each harbor gate lists a hotline and website to verify credentials. If a captain dodges safety questions, “don’t get on that boat.”

- Know your crowd. A 50-foot yacht is “a one- or two-bedroom apartment on the water.” Ideally, he advises that passengers should boat with people they know, instead of booking with strangers, as the vibe could be off. For instance, if you’re an introvert, don’t go on a boat with people who like to “turn up,” and conversely, if you’re one of those “turn-up” people, don’t go on a boat with a bunch of introverts, he said.

- Respect the weather. Gorgeous skies can hide high winds that rock you sick—or worse.

- Wear a life jacket. The cold and current can overtake strong swimmers.

For those unsure, larger tour boats along the river and Navy Pier offer a proper boating experience on the lake, minus the risk.

What comes next

In the wake of Black Yacht Weekend, Deese expects “random” Coast Guard inspections all summer. He welcomes them if they save lives and preserve a pastime his father introduced when he was eight.

Chicago’s Black boating community isn’t leaving the lake—and shouldn’t have to. But as Deese stressed, “You want to enjoy it. But you have to understand…You need to protect yourself at all times.”