“Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” is a new documentary film premiering on PBS on May 31, 2021, the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre. The film explores the events that destroyed a once prosperous and thriving community in Oklahoma. On May 31, 1921, a mob of white residents destroyed the Greenwood community of Tulsa, Oklahoma also known as “Black Wall Street”. Reported by Washington Post journalist, DeNeen L. Brown, and narrated by Emmy award-winning journalist, Michel Martin, “Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” traces the history of violence against Black People and uncovers the truth behind one of the worst incidents of racial violence in this country.

Featuring interviews with descendants, civil rights activists, community leaders, historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists, “Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” delves into this mass murder and destruction of a community and the fight for reparations for the survivors and their descendants. The documentary also looks at the efforts to uncover mass graves of the many unknown victims of this horrific tragedy.

THE HISTORY OF GREENWOOD

To understand this tragic event, one must understand the history of how black people came into such positions of agency during segregation. According to the 2001 Tulsa Race Riot Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Riot, During the Seven Year War, Indians tribes were forced violently from their land and given allotments of land in the south. These Indian tribes owned slaves. When slavery was outlawed the Indian Slaveowners gave their slaves land allotments since their slaves were registered as members of the tribes. The now freed slaves were landowners and many sought refuge and new opportunities in the land that would eventually be known as Oklahoma.

On this land, Black people built communities. Despite segregation, increased lynching’s and the outbreak of racial violence, the community of Greenwood, Oklahoma was thriving by the early 1900s. Historians estimate that in 1921 the Greenwood District had a population of ten thousand. Because of segregation, blacks were unable to shop outside of their neighborhoods, stay in hotels outside of their neighborhood, enjoy entertainment and leisure outside of their neighborhoods. So, these residents built their own and their black dollars were continuously recirculated in the community. Close to 40 blocks of a self-sustaining community where blacks held a surprising amount of agency. They were landowners, many were also gun owners having served in the World War, they were also entrepreneurs and businessmen. The commercial district along Greenwood Avenue was filled with the finest black-owned businesses. Hotels, small grocery stores, café’s, theatres, a roller-skating rink, the YMCA, a tailor, and cleaners, and more. Two black newspapers, The Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun, a post office, an all-black hospital, Frissell Memorial, an elementary school and high school, a library, and professional services such as doctors, dentists, lawyers, and realtors. That all changed on May 31, 1921.

A SINGLE INCIDENT ALTERS A COMMUNITY FOREVER

Dick Rowland, a young black teen entered an office building called the Drexel Building. He entered an elevator where a young white woman worked as the operator, Sara Page. According to the film, the elevator jerked, and Dick Rowland stumbled and touched Sara Page. As the elevator opened, she screamed, and Rowland fled. The police were called and the next day Rowland was arrested. The white newspaper, The Tulsa Tribune published a story on the front page saying Rowland was arrested for sexually assaulting Sara Page. That same paper also published an editorial titled “To Lynch Negro Tonight”. Ironically, the newspapers destroyed the articles published during these two days before archiving most of their other work on microfilm. That day as news of the article spread an angry mob of white men gathered outside the courthouse demanding law enforcement release him into their hands. Believing Dick Rowland was in danger of being lynched the men of Greenwood also gathered at the courthouse to protect the young black teen from people who they believe intended to lynch him. They arrived armed. There was a scuffle between two men and a shot was fired and a riot broke out. The black men were able to defend their community and protect Rowland, but it would not be for long. The black men were outnumbered by the white mob and they headed back to their homes. Reports suggest there were 75 black men defending their community against a white mob of 1500. This was the beginning of terror that would last over 18 hours.

After the incident at the courthouse, the Tulsa police deputized members of the angry mob, giving them weapons and ammunition. The white mob filtered into the community of Greenwood, looting businesses, and homes then setting them on fire. They murdered residents and took others into custody, holding them in detaining camps. Those held in these camps were only released if a white person accepted responsibility for their behavior. Those individuals were forced to wear Identification as well.

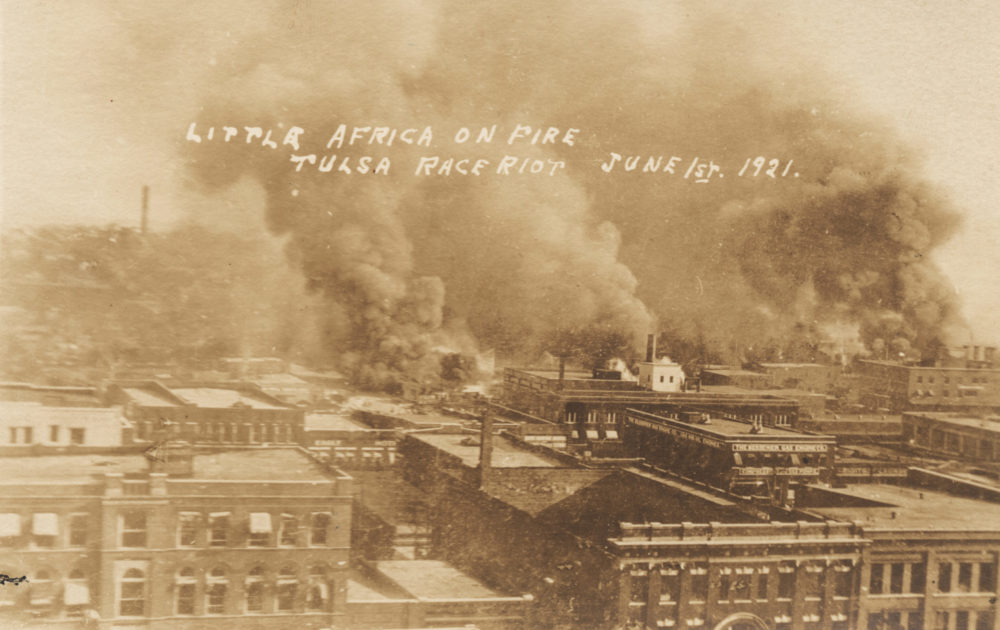

In just 18 hours, over 1200 homes were burned, over 200 homes were looted, two newspapers, a school, library, hospital, churches, hotels, stores, and more were completely burned to the ground or damaged beyond repair. Between May 31st and June 1st, thirty-five square blocks of the once prosperous community were destroyed. Historians estimate that up to 300 Black Americans were killed and over 10,000 black residents became homeless.

A JOURNALIST SEEKS ANSWERS

In “Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten”, Washington Post reporter, DeNeen Brown investigates this heinous act and why no one was ever brought to justice. She addresses the culture of silence in the black community with descendants and survivors who were unwilling to discuss the event and white guilt and shame associated with covering up this crime in the history books. As the nation grapples with equity and righting historical wrongs, DeNeen Brown talks with politicians, activists, and residents about reparations and the fight to uncover mass graves and identify victims using forensic anthropology.

In December 2019, an archaeological survey team reported the possibility of mass graves near the Canes Riverbank. The city of Tulsa began searching for the mass graves at the Riverbank and in Oaklawn Cemetery. “Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” tracks the search for mass graves by Eric Stover, Human Rights Investigator, and Researcher, Betsey Warner.

DeNeen Brown has roots in Tulsa and her interest in telling the story of the Tulsa Massacre started with a trip to visit her father and a subsequent lunch in Greenwood at Wanda’s Café in 2018. When she returned to Washington DC, she shared her experience with her editor who told her it would make a great story. She returned to Tulsa, meeting with activists and community leaders fighting for reparations for the Tulsa Massacre survivors and descendants. They took her to the area known as Black Wall Street and she saw all the plaques identifying all the buildings and businesses that once lined the street. It was during a visit to Oak Lawn cemetery where she says she felt the story in her soul. “As a writer, I’ve tried the tell the stories of people who aren’t often heard in mainstream media. I wanted to capture the emotion I felt in Tulsa and try to infuse the story that I was writing with that emotion. I could feel the pain of the generations impacted by that massacre. There is a heaviness and sadness to Greenwood. The place has so many lingering questions. It is like a haunting feeling, DeNeen Brown says.

THE LINGERING EFFECT OF THE MASSACRE

“Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” is a powerful documentary that will leave you stunned at not only the atrocity of the event but its aftereffects on a community and its people. The pain and the trauma and the weight of this atrocious event have been passed down through generations.

“Stories have power and if they are told they can change the future and provide some healing. My goal would be to finally find answers for some of the descendants of the victims and if they do find bodies, put those souls to rest”. -DeNeen Brown

“Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten” premieres on PBS on the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre on May 31st on PBS. Visit www.pbs.org or check your local listings for times.

Danielle Sanders is a journalist and writer living in Chicago. Find her on Twitter @DanieSanders20.