Members of the Utah National Guard were deployed to Washington in June 2020 in response to public protests and demonstrations. AP Photo/Alex Brandon

by Marcus Hedahl, United States Naval Academy and Bradley Jay Strawser, Naval Postgraduate School

On the campaign trail, former President Donald Trump has declared there are serious threats to the United States. First, he said, there is “the outside enemy, and then we have the enemy from within, and the enemy from within, in my opinion, is more dangerous,” as he told Fox News in an Oct. 13, 2024, interview.

He went on to say that “the bigger problem are the people from within. We have some very bad people. We have some sick people, radical left lunatics. And I think. And it should be very easily handled by, if necessary, by National Guard or, if really necessary, by the military.”

When asked on CNN about Trump’s remarks about using the military on U.S. soil, Mark Esper, one of five people who led the Defense Department during Trump’s presidency, said Americans “should take those words seriously,” most especially because Trump had already tried to do so when he was president.

As professors of military ethics, we worry that Trump’s actions while president, and his comments about his plans for a potential second term, may put the military in a tough position. The July 1, 2024, Supreme Court ruling giving the president immunity for official acts – potentially including as commander in chief of the military – would make that tough position even more difficult.

Response to demonstrations

In the summer of 2020, protests, including some violent ones, arose in cities around the U.S. in the wake of the May 25 murder of George Floyd. Then-President Trump announced he was considering sending the U.S. military into the streets of several American cities. He had already deployed some National Guard members in Washington in an effort to control the demonstrations there.

At the time, the two of us considered the possibility of dissent within the military hierarchy, saying that resistance would be most effective “if it were to come from those at the top.”

Indeed, many of the highest-ranking generals, admirals and Cabinet-level advisers resisted Trump’s requests to send the military to “beat the f— out” of protesters and “crack their skulls” – or even “just shoot them.”

Though Trump reportedly wanted to bring as many as 10,000 soldiers to Washington, fewer troops were deployed in the nation’s capital. No federal military personnel were used against public demonstrations in the U.S. that summer. Some National Guard troops were called up by state governors, not federal orders.

The reasons for civilian control

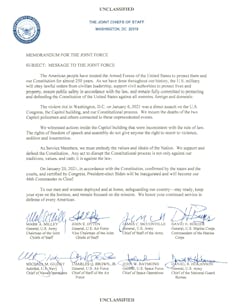

A Jan. 12, 2021, message from the nation’s top military officers reminds all service members that ‘We support and defend the Constitution’ – not any particular person. Joint Chiefs of Staff

For his potential second term, Trump says he wants to hire Cabinet and other government officials who will follow his orders without question, rather than people who might try to prevent his worst inclinations from being enacted.

Questions about dissent and disobedience will therefore likely fall on those at more junior levels of military service in a second Trump administration than they did in the first.

The U.S. military has long been dedicated to the principle of civilian control. To minimize the chance of the kind of military occupation they suffered during the Revolutionary War, the country’s founders wrote the Constitution requiring that the president, an elected civilian, would be the commander in chief of the military. In the wake of World War II, Congress went even further, restructuring the military and requiring that the secretary of defense be a civilian as well.

For that reason, in a time of increasing political polarization, military educational institutions are focusing even more explicitly on the oath military members take to the Constitution, rather than to a person or an office.

As the Joint Chiefs of Staff reminded the military after the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection, and just before the inauguration of Joe Biden as president, military personnel serve the nation’s interests, not those of a politician or a political party.

Nonpartisanship could become partisan

When faced with a potential order to deploy the U.S. military within the nation’s borders, however, service members may find themselves in a situation where upholding the military’s tradition of staying out of politics could itself appear partisan.

Military members have a duty to obey orders from superior officers. But as military ethicists, we recognize that the content of an order is not the only factor that determines whether it is a moral one.

The political motivation for an order may be equally important. That’s because the military’s obligation to stay out of politics is deeply intertwined with the mutual obligation of civilian officials not to use the military for partisan reasons.

If an elected official were to attempt to use the military for obviously partisan ends, the decisions of military personnel to either follow the order or resist it would open them up to accusations of partisanship – even if their actions were attempts to protect the military’s strict partisan neutrality.

At the nation’s founding, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson worried about a military that would be loyal to a particular leader rather than to a form of government. James Madison was concerned that soldiers might be used by those in power as instruments of oppression against the citizenry.

Trump has said the National Guard or the military could “easily handle” political protesters. He has recommended one “really rough, nasty” hour of police violence to curb criminal activity. He has expressed a desire for military officers to be obedient to him and not the Constitution.

It’s not clear that military members could follow those kinds of orders and remain nonpartisan. By refusing to follow orders about military deployment to U.S. cities for political ends, members of the armed forces could actually be respecting, rather than undermining, the principle of civilian control. After all, the framers always intended it to be the people’s military – not the president’s.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Risks for military members

There is a long line of military heroes who had the moral courage not to follow immoral orders. In fact, it was a junior officer who first exposed the widespread use of torture in the global war on terror.

That particular example may be useful to consider in the weeks and months ahead, given the significant effort at the time to argue that some of those immoral orders could nonetheless be legal.

Recently, some of Trump’s former military advisers have raised concerns about the the potential use of U.S. troops in American cities. But several of his civilian advisers have already recommended being less reticent about finding legal means to deploy the military within the country. And a July 1, 2024, Supreme Court ruling gave the president criminal immunity for official acts – which almost certainly include giving orders to the military.

Regardless of who wins the 2024 presidential election, there will likely be significant protests over policy – perhaps even over the results themselves. If the military is ever called in because of those actions, military members would have to consider whether they could ethically follow the orders to do so. To be ready to answer these important questions, they have to consider them now.

We often ask our students to imagine themselves in numerous different ethical situations, both real and hypothetical. In the present circumstance, we believe one set of ethical questions could quickly become very concrete for those serving:

“Would you obey an order from a president – a particular president giving an order for a particular reason – to deploy to a U.S. city? What might it mean for the nation if you did? And what might it mean for American democracy if, in some circumstances, you were brave enough not to?”

Many Americans claim to venerate military men and women, thanking them for their service and standing to celebrate them at sporting events. They may need much more support than that from the American people, and soon.

The academic views expressed in this article are the views of the authors alone and should not be read as endorsing any candidate for office. They do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Naval Academy, the Naval Postgraduate School, the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense or any other entity within the U.S. government; the authors are not authorized to provide any official position of these entities.

This article contains some material previously published on June 11, 2020.

Marcus Hedahl, Professor of Philosophy, United States Naval Academy and Bradley Jay Strawser, Professor of Philosophy, Naval Postgraduate School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.