Once in a while we have the opportunity to witness greatness in our lifetime. Some of us are blessed to surround ourselves with people who exemplify acts of greatness everyday while others are challenged with the definition. Who determines how great a person is based on one’s interpretation?

Once in a while we have the opportunity to witness greatness in our lifetime. Some of us are blessed to surround ourselves with people who exemplify acts of greatness everyday while others are challenged with the definition. Who determines how great a person is based on one’s interpretation?

One may argue greatness is determined by a person’s deeds–bringing people together for a common good.

As a small boy in the deep South of Savannah, Ga., a young John Sengstacke was surrounded by the family business and steered by his interest in his father’s local newspaper, the Woodville Times. His interest was immediately noticed by his uncle and founder of The Chicago Defender, Robert Abbott, who settled in Chicago after earning his law degree from Hampton Institute. From establishing the paper in 1905 to becoming a millionaire and one of the country’s leading publishers, Abbott was designing the blueprint that Sengstacke was destined to follow throughout his lifetime.

Following in the footsteps of Robert Abbott, Sengstacke attended his uncle’s alma mater, Hampton Institute. During the summer, he worked at the Defender under the guidance of Abbott. When he graduated in 1934, he was offered a full-time position at the Defender. To ensure a safe passage from down South to Chicago, Abbott recruited friend and activist Mary McLeod Bethune to travel with him. While on the train, Bethune and George Washington Carver schooled the college graduate on the responsibility he would carry in such an important role.

A couple years later, his role progressed as Vice President and General Manager of The Robert S. Abbott Publishing Company. Sengstacke steadily gained the trust of Abbott. Recognizing how a collaborative effort by other Black-owned newspapers could be more powerful than an individual one on its own, on the day of Robert S. Abbott’s passing, Sengstacke brought together a group of the nation’s leading African- American newspaper publishers in 1940 to establish the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA).

A couple years later, his role progressed as Vice President and General Manager of The Robert S. Abbott Publishing Company. Sengstacke steadily gained the trust of Abbott. Recognizing how a collaborative effort by other Black-owned newspapers could be more powerful than an individual one on its own, on the day of Robert S. Abbott’s passing, Sengstacke brought together a group of the nation’s leading African- American newspaper publishers in 1940 to establish the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA).

As a founding member, he would serve for seven terms—establishing more economic empowerment in advertisement for members around the country.

Today, the NNPA remains one of the most influential organizations with nearly 200 Black-owned publications including The Chicago Defender.

The power of the Defender reached beyond the urban cities of the North. As the Jim Crow South tightened its grip on Blacks, the paper was smuggled on trains by Pullman Porters traveling below the Mason-Dixon line. Many would wait patiently as bundles would be thrown over the railings through rural parts of Southern states—with news of jobs and a better quality of life in Northern cities such as Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland. People flocked in the thousands searching for a better life and a better way in urban cities, fueled by stories of prosperity and hope in the Defender.

A Part of Change

A Part of Change

As the paper reported on various issues that hit at the core of our community, Sengstacke knew it was more than simply reporting the news—it was more important to become a part of the change. The Chicago Defender was at the frontline of shaping the narrative and Sengstacke knew firsthand his responsibility as a publisher to bring his input to Washington, D.C.

His interaction with President Franklin D. Roosevelt influenced Black reporters to attend White House press conferences and he helped to open up more government jobs on a federal level to African Americans. Applying that same diligence, Sengestacke would play a much bigger role for President Harry Truman, sitting on a special White House commission to integrate the military in 1949. Up until this time, Black servicemen fought courageously in both World War I and World War II sacrificing their lives for the same democracy and freedom that was denied on U.S. soil. Sengstacke was part of making sure the armed forces dismantled their segregation policies for African American citizens.

Sengstacke also supported the efforts of integrating Major League Baseball in 1947 with Jackie Robinson’s becoming the first Black professional player, playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Understanding the power of preserving Black newspapers, Sengstacke acquired the Michigan Chronicle (Detroit, Michigan) and the Tri-State Defender (Memphis, Tennessee) in the 1950’s—and he transitioned The Chicago Defender from a weekly to a daily paper. He believed that in order to keep up with other daily mainstream papers, the only way to compete was to provide readers the paper on a daily basis. The Sengstacke Newspapers would go on to purchase the Pittsburgh Courier in 1966, reestablishing the historical paper as the New Pittsburgh Courier.

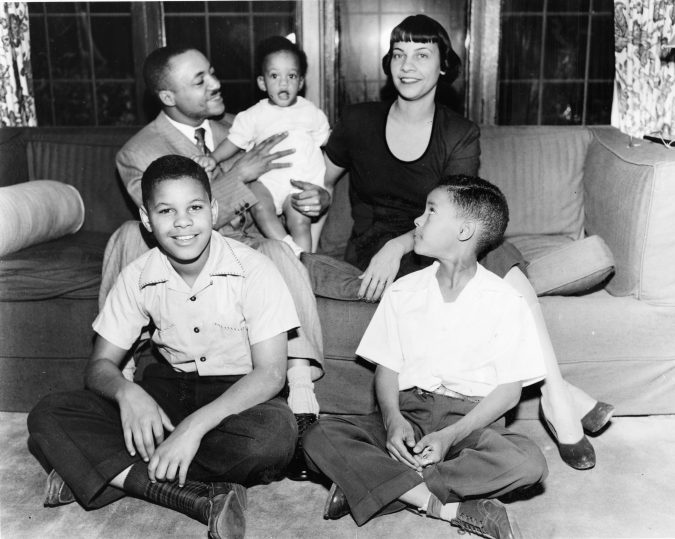

A Family Man

A Family Man

Establishing his legacy was not the purpose of Sengstacke’s mission as much as was his duty and responsibility as a family man. Married to Myrtle Elizabeth Picou-Sengstacke, the couple had three children: John H. Sengstacke III; Lewis W. Sengstacke and Robert A. Sengstacke. Maintaining the tradition of youth empowerment, Sengstacke continued his uncle’s mission as “protector of children” by establishing The Chicago Defender Charities in 1945—the producer of the Bud Billiken Parade. Since its inception in 1929 by Abbott, the day-long event has grown to become the largest African American parade in the U.S. and the second largest to Macy’s annual Christmas parade in New York City.

Every second Saturday of August, the parade is the “beacon of light” for many youth and families who gather along Martin Luther King Drive cheering on their favorite high school bands, dance groups, community organizations and dignitaries.

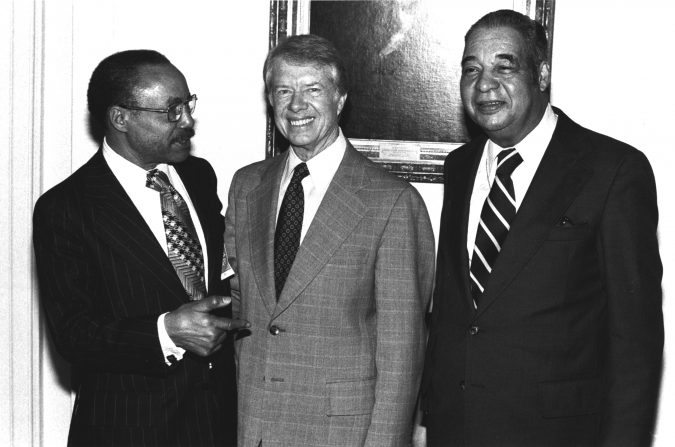

There are countless photographs of John H.H. Sengstacke throughout American historical archives as the quiet Black businessman rubbed elbows with many historical figures from every walk of life. But unless you’ve lived during an era that impacted the Civil Rights, arts and cultural movement—many would not understand the vital role Sengstacke played.

There are countless photographs of John H.H. Sengstacke throughout American historical archives as the quiet Black businessman rubbed elbows with many historical figures from every walk of life. But unless you’ve lived during an era that impacted the Civil Rights, arts and cultural movement—many would not understand the vital role Sengstacke played.

Sengstacke’s Grand-nephew and Director of Development at The Chicago Defender Charities, Marc Sengstacke, reflects on his uncle’s influence.

“One of the things that was the most amazing to me is when I was with him face-to-face and listened to him talk about the people he knew personally such as presidents, CEOs of major organizations and major politicians. As I heard him talk about that and I’m looking at him, something in me is saying, ‘Wait a minute, this is not some stranger talking about all of the powerful, rich famous people he knows—this is my uncle to whom I’m connected to by blood,’” says Marc Sengstacke.

A ground-breaking move that has had an avalanche of positive results in helping millions of African Americans in the workplace was Sengstacke’s helping to shape the Affirmative Action law with Congressman Dawson in the 1940s. Appointed by John F. Kennedy, Sengstacke joined the National Alliance of Businessman. He would sit in on many meetings and offer his advice and guidance.

It wasn’t until President John F. Kennedy’s administration when it was voted into law, but the publisher of the largest daily newspaper was never mentioned on his influence and work on this important piece of legislation.

To illustrate Sengstacke’s influence, Marc Sengstacke recalls a conversation he had with Judge Benton Parsons, the first African American to serve as a United States federal judge in the U.S. District Court in 1961 and until his death in 1993.

“Judge Parsons told several of us that one morning he woke and got a phone call from President Kennedy. The president was asking him if he wanted to be appointed to this federal judgeship. Judge Parsons was telling us when he had this conversation with President Kennedy he was trying to figure out how to get out of the appointment. He was hesitant on taking it and mid-way into the conversation he says, ‘Mr. President there’s a gentleman by the name of John Sengstacke who I usually talk to before I make a major decision.’ The president says, ‘Oh is that right? Well, Mr. Sengstacke is sitting across the desk from me right now. Would you like to talk to him?’ President Kennedy handed the phone to Uncle John. Judge Parsons heard Uncle John’s laugh. I could just hear that laugh because I heard it so many times,” says Sengstacke.

From championing the integration of the military; becoming one of Hampton University benefactors; participating on several presidential committees from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Lyndon B. Johnson—John H.H. Sengstacke’s fingerprint has a lasting effect on African American’s successful journey. His countless contribution to preserving social services and amenities within Chicago’s Black community including raising $50 million for Provident Hospital (managed under Cook County Hospital, the health center, serving thousands of patients, still bears his name.)

From championing the integration of the military; becoming one of Hampton University benefactors; participating on several presidential committees from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Lyndon B. Johnson—John H.H. Sengstacke’s fingerprint has a lasting effect on African American’s successful journey. His countless contribution to preserving social services and amenities within Chicago’s Black community including raising $50 million for Provident Hospital (managed under Cook County Hospital, the health center, serving thousands of patients, still bears his name.)

On May 28, 1997, Sengstacke died at 84. In 2007, Real Times Media, Inc. bought the family of publications the Sengstacke family managed for nearly nine decades. Twenty years later, after the silent giant’s passing, his granddaughter and Executive Director for The Chicago Defender Charities, Myiti Sengstacke-Rice, shares fond memories of him and his love for their family’s Michigan retreat.

“He would always call me ‘the boss’ and I would always call him ‘the boss boss’. That was our little thing. One of his favorite things to do—he would like to go out to the country. He would go and relax in Michigan—in an area called Buchanan. He would like to get away from the city. Those were some of my fondest memories of him,” she said.

Pastor Bill Winston of Living Word Ministries became familiar with The Chicago Defender as a young boy when it was delivered to his home in Tuskegee, Ala. He was inspired by the shining examples of the achievements by African Americans.

Pastor Bill Winston of Living Word Ministries became familiar with The Chicago Defender as a young boy when it was delivered to his home in Tuskegee, Ala. He was inspired by the shining examples of the achievements by African Americans.

“John Sengstacke was like Booker T. Washington. He wanted to make an impact on the world by adding value. He knew it was not only persistence but also abilities that were needed to break through the wall of segregation and inequality,” Winston said. “The key for the African American community is not to lose the ground, or hope, that was gained through the huge contributions and accomplishments of leaders like John H.H. Sengstacke. It’s extremely important that this ground is not lost. Not lost in African American publishing. Not lost in aviation, with the decline in black pilots. Not lost with African American banks, as in recent times. Not lost with historically black colleges and universities.”

John H.H. Sengstacke’s life is a reflection of hard work, tireless sacrifice and a love for Black people that is unrivaled to this day. From close ties to Chicago’s political powerhouse the Daley family to chronicling the city’s first Black mayor, Harold Washington, Sengstacke contributed to the narrative of Black history—American history.

There lies the true definition of “greatness.”

Harmony Health Plan, Inc. a Wellcare Company will present the Defender Charities with a special gift in honor of John H.H. Sengstacke and his advocacy for healthcare in the Chicago community at Thursday’s special fundraiser. An unveiling of the Sengstacke suite will be in the legendary Chicago Defender 2400 S. Michigan Ave. building.

Follow Mary L. Datcher on Twitter