When Emmett Till’s mutilated body was transported back to Chicago for his funeral, some 100,000 people stopped by Bronzeville’s Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ to pay respects to the 15-year-old boy who was brutally tortured and murdered for whistling at a White woman.

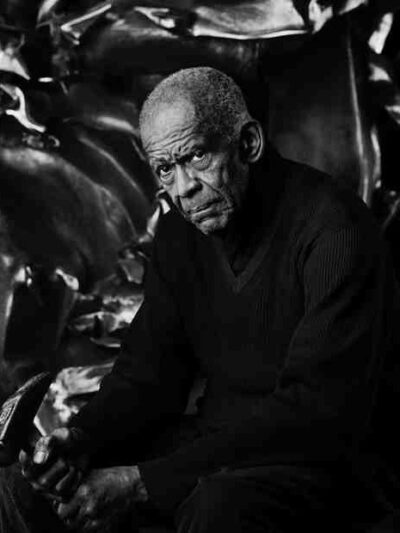

Among those who attended his open-casket funeral was a burgeoning artist named Richard Hunt, who would emerge from the South Side of Chicago as one of the most notable sculptors in American history. Hunt passed away peacefully this past Saturday at his Chicago home at the age of 88.

Hunt, who would gain renown as the foremost African-American sculptor of the 20th Century, recalled how attending Till’s funeral would influence his artistic expression and catalyze a lifelong commitment to civil rights within him.

“What happened to [Till] could have happened to me,” said Hunt, who grew up two blocks from the Till family in Chicago’s Woodlawn community.

Born in Chicago on Sept. 12, 1935, Hunt was the younger of two children born to Howard and Inez Henderson Hunt. His father was a barber, and his mother became the first Black librarian in Chicago. In his young life, notes the Smithsonian American Art Museum, he became interested in politics from listening to conversations at his father’s barbershop. He developed a love of reading and classical music from his mother.

He started drawing as a child, but that pursuit blossomed when he set up a studio in his bedroom in 1950 and began to model in clay. He was immersed in the arts from the historic South Side Community Art Center, the Junior School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the city’s public museums.

A 1953 Art Institute of Chicago exhibition, “Sculpture of the Twentieth Century,” deeply impacted him. He studied artworks made of welded metal and was influenced by great masters, including Julio Gonzalez, Picasso, David Smith and Alberto Giacometti. Hunt attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and focused on sculpture.

He gravitated toward abstraction, the kind of art that isn’t concerned with depicting scenes or worldly objects but with concepts and ideas expressed through composition, line, plane and pattern.

Hunt also drew inspiration from his natural environment, including animals, trees and plants, according to a Nov. 1970 Chicago Defender article on Southern Illinois University at Carbondale purchasing one of his sculptures.

Richard Hunt’s Sculptures: His Enduring, Indelible Impact

While many artists strive to make an indelible mark on the human imagination, fewer can bring that ideal to reality where their work leaves a lasting impression on the physical spaces they occupy.

This is what Hunt accomplished.

According to his website, he has made the most significant contribution to public art in the U.S., having more than 160 public sculpture commissions in prominent spaces across 24 states and Washington, D.C.

His presence in Chicago, his hometown, is even more palpable, as there remain more than 30 examples of Hunt’s sculptures in and around Chicago’s libraries, community centers, universities, apartment houses and office buildings.

Nowhere is his mark more indelible than through the towering, 35-foot-high Ida B. Wells Light of Truth National Monument in Bronzeville on the South Side.

Weighing in at over 14,000 pounds, this truly abstract marvel features a torch formed in twisted metal that hovers above three columns – the result of 13 years of fundraising and planning.

The sculpture, which sits on land where the Ida B. Wells Homes used to be, has become a Chicago landmark.

Hunt’s masterpiece, “Hero Construction,” is also showcased prominently on the grand staircase at the Art Institute of Chicago. According to Hunt’s website, former President Obama selected him as the inaugural artist to craft a piece, “Book Bird,” for the soon-to-be-completed Obama Presidential Center.

Hunt has also created major monuments and sculptures for notable historical figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Jesse Owens, Hobart Taylor, Jr. and Mary McLeod Bethune.

As the Smithsonian noted, Hunt utilized sculpture in public spaces to “bridge the gap between abstract art and the black experience in America.”

A private funeral service for Hunt will be held in Chicago. There are plans for a Spring celebration of Hunt’s art and life that will be open to the public. However, dates have yet to be announced.

Hunt is survived by his daughter Cecilia, an artist, and his sister Marian, a retired librarian, both of Chicago.