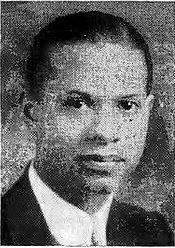

Steve Carper is a historian of popular culture. He researched Jay Jackson and compiled a unique commentary on Bungleton Green. The commentary uses illustrations from Jay Jackson, originally published in the Chicago Defender. January 6 was the superhero’s 76th birthday. In recognition, the Chicago Defender is pleased to feature part 2 in our 3 part series, “Jay Jackson and The First Black Superhero” by Steve Carper.

THE FIRST BLACK SUPERHERO…Continued

Prince Whipple emerges out of thin air to frighten off the black gang teens. The next week he hands the Mystic Commandos a magic Zulu ring they can use to call him whenever they’re in trouble. Jackson was way ahead of Jimmy Olson’s Superman signal watch with this.

The storyline shifts to other contemporary issues, far distant from science fiction. Jay Jackson played a long game. By 1943, the U.S. was completely on a war footing. Millions of men enlisted or drafted while industries retooled into defense plants. Many working overtime to supply what President Roosevelt proclaimed “the arsenal of democracy.” Wartime factories required more from millions of workers than the armed forces. As a result, jobs opened for women and people of color to work side-by-side with the remaining white men. Jay Jackson’s drawings personalized the headlines on the pages of Defender. Despite the “we’re-all-in-it-together” propaganda the government spewed, the reality of the 1940s was that white workers resented blacks. They often relegated black workers to menial tasks. They were also seldom promoted if that put them in authority over whites.

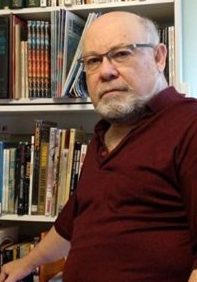

Jay Jackson added melodrama to unpleasant reality by introducing a German spy ring led by the uber-Teutonic “Monocle.” In July he captures Bung and a few Commandos. Monocle then imprisons and tortures them in Germany in his “private concentration camp.” Readers were expecting some heroic derring-do and a miraculous escape. Jay Jackson overturned conventions again, in the most eye-popping way. They’re tortured and they die, their bodies were thrown into a ditch.

Jay Jackson left reality, now committed to the science-fictional miracles he soaked up in the Ziff-Davis world. A side plot concerns an anti-Nazi German scientist who invents a time machine. He intends to escape from Germany’s certain doom in the war. His shrewish wife is willing to travel into the past with him but insists on taking along slaves to serve her. Jackson puts the unsayable into the mouth of the scientist, whose double meaning would be obvious to his readers. “My dear, we must become as certain other folk .. talk of freedom for all but think of it as being reserved only for the master race!” The Mystic Commandos will do nicely as her slaves. If the Monocle plans on killing them, her husband must invent a resurrection device to bring them back to life. The genius scientist solves this impossible problem in a moment. He creates a poison that simulates death. Since the Commandos are having their toenails pulled out outdoors, he uses a blow dart to deliver his poison. The Monocle believes they were too weak to stand up under torture and throws them into that ditch. The “old scientist” steals them out of the ditch and reverses his drug.

The rest of the characters land back in 1778 America. 1778 America is not a place black characters or their suspicious-looking supposed master can stay. The Commandos get their turn at derring-do and miraculous escapes for a few months. They wait until the scientist can repair his time machine, damaged during a fracas. George Washington was unbesmirchable in wartime. Jackson could invent many evil slave owners for the Commandos to fight and foil, history as both social commentary and wish-fulfillment fantasy in the best comic strip tradition.

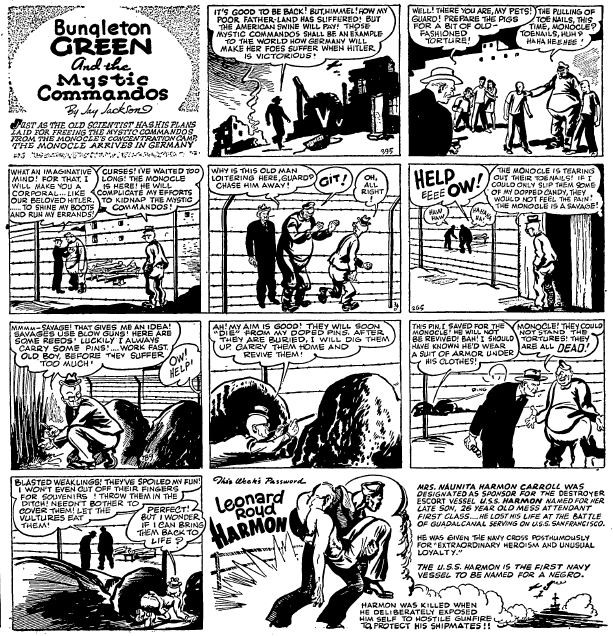

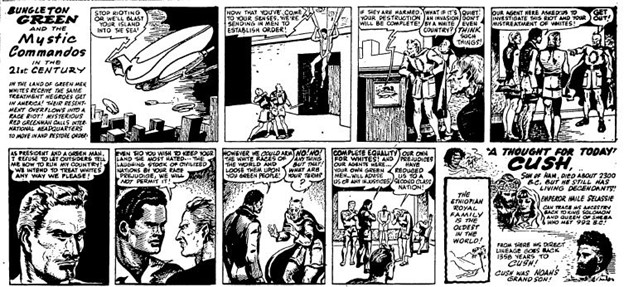

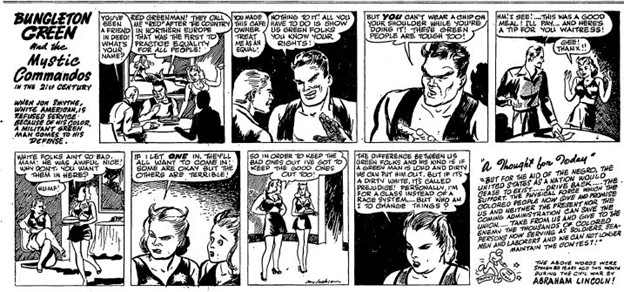

Building a time machine from 1778 parts was no easy task and the old scientist forgave a slight glitch. When he turns it on Bung and the Commandos find themselves in Memphis, TN, not in 1943 but 2043. The future is a different realm from that of the known past. It belongs to science fiction. Jackson hammers home the science fiction connection to the famous comic strip Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. He does this by changing the name of his strip to Bungleton Green in the 21st Century.

Portrayed in science-fictional terms, The 21st century includes a remote televiewer, a flying woman, and anti-gravity tubes.

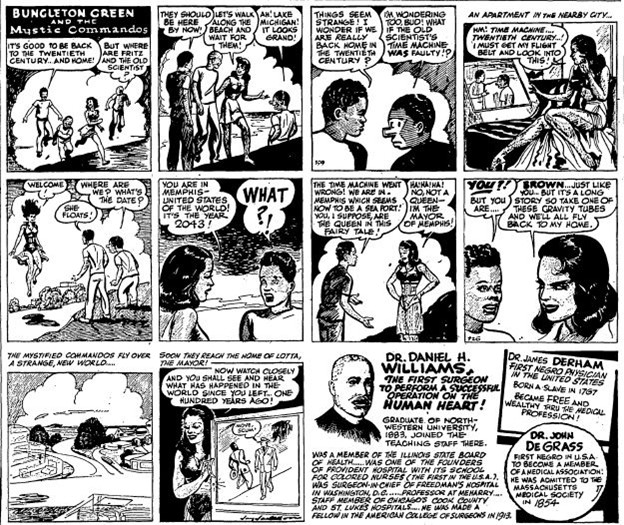

If Jay Jackson’s 1778 was the world not emphasized by the patriotically simplistic history books, his 2043 was a device for bitter commentary on the conditions of 1943; a world of role reversal in which whites are at the bottom, in every way treated as badly as blacks had been throughout American history. The past was known; the future could be written with infinite possibilities, likely or not. Displacing the current world into an allegorical future was a lesson from Amazing Stories that a clever writer could safely mine while winking at readers who got the double meanings.

In the timeline of Jay Jackson’s future, a massive earthquake raised an ancient continent from the seabed, wiping out much of North America. The continent was ruled by green people, who become horrible oppressors of the whites when they encounter them. Blacks existed in the middle, there to continually point out the irony.

What’s left of America, is a utopian paradise of equality in this future. A scientist in this timeline’s 1943 invented a fountain of youth pill. He uses it to bribe old Southern bigot senators to vote to end Jim Crow. The President decides to send a delegation to convince the greens that “there can be no peace without unity and brotherhood.” Lotta, the brown-skinned mayor of Memphis, takes along a white man, a yellow man, and black Commando Bud. Jon Smythe, the white man, is the narrative device who wanders around confused by this upside-down world of green domination. “What have we white people ever done to have to suffer such rotton [sic] discrimination?” he asks. Life in an egalitarian country has never introduced him to the banality of racism. For Jackson, racism was best treated as a product of ignorance that could be swept away by education and good examples. This great hope would continue to pop up no matter how much evidence he himself presented against its fulfillment.

The green world is one too dangerous for Jon to remain in, but their racist laws give him no way to leave either. Even their planes have Jim Crow sections for whites; without enough whites to fill the section, Jon can’t board. The brown and yellow delegates go but Bud stays behind to help protect Jon, simplifying the parable to stark terms of literal black and white. They flee and travel to the northern part of the green continent, where people are not reputed to be as prejudiced as the southerners.

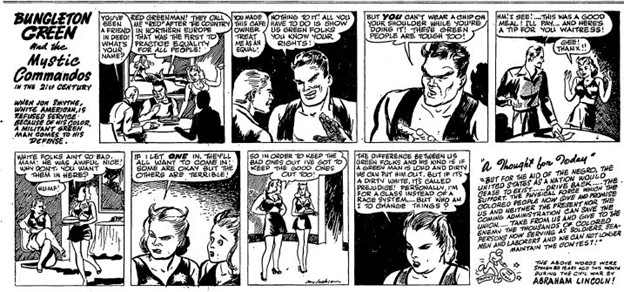

The northerners have civil rights laws: they find subtler ways around them. When Bud and Jon try to eat in a restaurant they can’t get a menu. When they insist on their rights they’re asked for their membership cards. The restaurant is a private club, a common dodge of the 1940s era to refuse black patrons. To their rescue comes Red Greenman, a green northerner who believes in equality. “Red” isn’t the color of his hair, it’s symbolic of “the country in northern Europe that was the first to practice equality for all people.” After the reds threaten the invasion the factory has been preparing for, the greens call upon all their people, even the “chalkies,” to resist. Jon grumbles, “These green men are threatened with war and still treat us loyal whites in this country worse than they do the enemy!”

As the north had a few sympathetic greens, it had rebellious whites. These are whites so bitter from decades of oppression that they teetered on the edge of rioting. Contemporary readers would identify: deadly race riots in Detroit and Harlem killed three dozen people in 1943. Russia invades the green continent to force equality on the greens. Forced equality works in the future. Within weeks discrimination is not legally abolished but forgotten by green and white alike. Bud and Jon catch a stratorocket, itself a science-fictional device, for America.

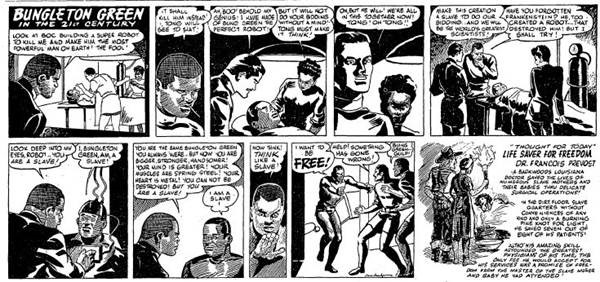

Readers hadn’t seen Bungleton Green for a year, but on November 25, 1944, he makes a dramatic return to the strip. He has been stuck in 21st century America, a paradise, true, but one without his wife, Beebe. Mad scientists who want to experiment on a body no one will miss kidnap him. They want to turn Bung… into a robot superman!

Jay Jackson’s science was murky at best. All we see is Bung laid out on an operating table and anesthetized. When he awakens, he has the body of a Joe Louis. “You are the same Bungleton Green you always were,” says one of the scientists. “But now you are bigger, stronger, handsomer! Your mind is greater! Your muscles are spring steel! Your heart is metal! You cannot be destroyed!” Whether this is literal or figurative isn’t clear, because the new Bung is never again referred to as a robot after the strip leaves the scientists behind. Still, the now super Bung has most of the powers of the early Superman. Jackson revealed himself to be as familiar with comic strips and books as he was with prose media. The scientist’s transformation of a puny man into a pinnacle of perfection was reminiscent of Captain America’s origin. In those days, comics were a giant community stew into which everyone contributed ideas for the taking, reworked with individual touches.

Bad guys never learned from experience: even in the 21st century, evil scientists take their fiendish plans one step too far. “You are a slave!” one scientist tells Bung, trying to brainwash him. “Think like a slave!” How does a slave think? Not as the master imagines.

“I want to be FREE!” Bung yells, in a panel as powerful as any in comics history. Freedom clears his head. The now superman easily overcomes the scientists, who had fortuitously earlier wrested the secret of a time machine from Bung’s brain. Bung immediately demands to return home and to the wife, he left behind. The rest of the Commandos refuse to go back to the racist hell that they left; the utopian America of the 21st century is far preferable. The Mystic Commandos disband and Bung travels back in time accompanied only by Boo, the scientists’ beautiful captive who sided with Bung against them.