Hired by the Chicago Defender in 1933, Jay Jackson is one of the top cartoonists in Black media. Becoming the head cartoonist in 1936, he created a series of editorial comic strips with strong social commentary. On November 28, 1942, he revived the Defender’s signature strip, Bungleton Green. Historians call the strip “the oldest, longest continuously running black comic strip.”

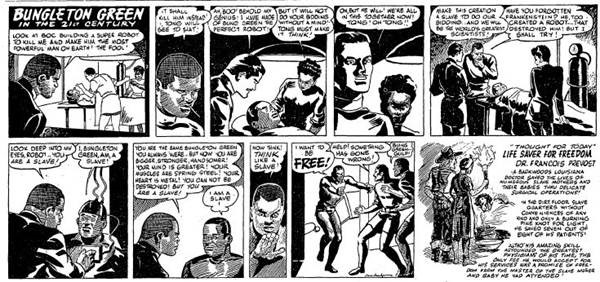

In Jackson’s hands, the lead character, Bung, became a pillar of the community. Bung started a youth center to address the problems caused by parents absent at war or working during wartimes. This was a serious issue in 1942. Eventually, Jay Jackson moved the strip into fantasy and science fiction. Bung was killed and revived, taken by a time machine to 1778 to comment on America’s shameful history of slavery. Jackson then moved the character to the 21st century, when America was a colorblind utopia. Yet, a continent of green people treated whites in ways every black person would recognize in the 1940s. Jay Jackson’s comics were forward-thinking as there was nothing of this caliber previously done in any comic strip. The social commentary is still appropriate today.

Steve Carper is a historian of popular culture. He researched Jay Jackson and compiled a unique commentary on Bungleton Green. The commentary uses illustrations from Jay Jackson, originally published in the Chicago Defender. January 6 was the superhero’s 76th birthday. In recognition, the Chicago Defender is pleased to feature this special 3 part series, “Jay Jackson and The First Black Superhero” by Steve Carper.

Jay Jackson and The First Black Superhero-Part 1

Written by: Steve Carper

Jay Jackson introduced the world to the first black superhero on January 6, 1945. The oldest and longest-running Black Comic strip ran in the pages of the country’s leading black newspaper, The Chicago Defender.

Bungleton Green, the name of the character and the strip, became the embodiment of the black ideal. “Bung” was a man who was equal, even superior, to whites whose relentless oppression Jay Jackson fought. It is no coincidence Jackson set his character during World War II. The time was ripe. Jackson wanted to remind Americans of black Americans’ unequal status fighting in the war and supporting war efforts. The result was some of the most potent social commentary ever put into comic form, with excoriations of white supremacy, bigotry, and systemic racism. The comic strip resonates with current events happening in the country.

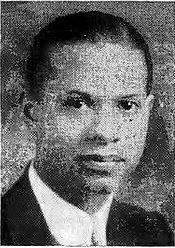

Born on September 10, 1905, in Oberlin, Ohio, Jackson dropped out of school at thirteen to drive spikes for a railroad. He moved to Pittsburgh, working in a steel mill. After marrying young, Jay Jackson attended Ohio Wesleyan College for a year. He enjoyed a brief and mostly losing stint as a boxer. Better fortune came his way when he dropped of school to start a sign-painting business. In Pittsburgh, Jackson became a featured artist for the Pittsburgh Courier, another historic black newspaper, creating two comic strips a week.

The Great Depression caught up with Jackson in 1933. He caught a break when hired to produce the mural in the Old Mexico building at the Chicago Century of Progress Exposition. Jackson also reconnected with the Courier with a series of illustrated poems.

Elmer A. Carter, the editor of Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, a publication of the National Urban League, sent a letter to the editor that ran on June 17, 1933.

“I have noticed the work of Jay Jackson in the Feature Section of The Pittsburgh Courier, and I wish to congratulate The Courier and Mr. Jackson for what to me is the best presentation and the best cartooning that I have seen in a Negro newspaper. As a matter of fact, Jackson’s work is not surpassed in this field by any cartoonist in any newspaper, white or colored”.

A rave like that will get you a job even at the lowest point of a Depression. The Defender made him assistant to lead cartoonist, Henry Brown. Allowed to continue freelancing, Jackson supplemented the low pay with “a three-year contract from a New York publisher to fill up a half-page each week in his magazine section.” It most likely was the black New York Amsterdam News, with whom he worked for thirteen years.

Jackson became head cartoonist sometime around 1936. His editorial cartoons are scathing indictments of prejudice, Jim Crow laws, and unequal opportunities for blacks. You can see his palpable anger in every pen stroke. In addition to his duties of creating original cartoons and strips, he took over the Defender’s seminal strip production, Bungleton Green, in 1934. Created by Defender staff cartoonist Leslie Rogers in 1920, Bungleton Green was the first and longest-lived black comic strip.

The cartoonists often treated the strip almost as an afterthought. With Bung’s looks, personality, and marriage status changed at whim and adventures abandoned halfway through to take him down a new road. “Bung,” as he was usually known, was quite literally the proverbial little man, generally desperately poor but happy-go-lucky. Still, sometimes a sharp operator who kept clawing himself to the top, variously portrayed as a stereotype, a caricature, or a commentary on everyday life.

Evidence suggests Jackson didn’t care at all for the silly strip, preferring his brand of social commentary in his strips. Bungleton Green often failed to appear, and Jackson had his assistant, Daniel Day, did many of the strips starting in 1939.

The date is significant. The year before, Jay Jackson was given an unexpected freelancing opportunity, alleviating his boredom at work and his often-precarious financial situation. In a world that had not yet seen the introduction of Superman, the path to the first black superhero started with the other venue for weird science and fabulous imagination: science fiction. Amazing Stories, the now-legendary first science fiction (SF) magazine founded in 1926, reached an all-time low in circulation in 1938, when Chicagoan William B. Ziff purchased it. He was a cartoonist himself, studying at the Chicago Art Institute a decade before Jackson attended. He also found that cartooning didn’t pay well, so in 1920, he founded an advertising agency at the age of 22.

One of W. B. Ziff Company’s first acts as a business was to exploit an untapped market niche. Most large cities had a black newspaper. Most white advertisers ignored them. The white Ziff realized he could become a central clearinghouse for advertising in black newspapers nationally and thereby entice large white corporations as clients. Soon he had a near-lock on the market, pushing aside black pioneers like Claude Barnett. With both headquartered in Chicago, Ziff-Davis and the Defender had close ties. Either he or the art director of his company’s many magazines, Herman R. Bolin, turned to local artists to provide illustrations for Amazing. Jackson was known as good, versatile, and fast, all the utter necessities of a freelancer.

His drawings illustrate three stories in Palmer’s first, June 1938, issue of Amazing. Given bimonthly magazine lead times, Jackson likely got hired about five minutes after the ink dried on the purchase contract and turned in his completed artwork not much later. Over the next four years, his work appeared in more than three dozen issues of Amazing and its companion, Fantastic Adventures, often for multiple stories.

Jay Jackson was the first black artist published regularly in science fiction magazines. He wasn’t a fan favorite in the beginning: the savvy readers noticed his lack of genre experience. Eventually, the comments in the letter columns warmed. His comic stylings fit the many humorous stories that Palmer doted on. He was one of the rare artists included in the “Introducing the Author” column. A photo ensured that readers knew that Jackson was a black man who had attended college, was the proud father of a teen daughter in his suburban home, and had a decade of varied art experience.

Jackson absorbed all the tropes of 1930s science fiction: time machines, superbeings, rocket travel, mad scientists, and weird inventions. Even better for a cartoonist, he realized that science fiction gave writers a unique ability to comment on contemporary America by safely displacing the action to another world or time.

He displaced himself first. In 1942 he stopped drawing for Ziff and devoted himself to reviving the cartoon page at the Defender. That page changed abruptly on November 24, 1942, with a new Bungleton Green that would rely upon the science fiction devices and tropes Jackson soaked up during his four years. It ultimately leads to a startling crescendo: a black superhero avenging the wrongs of American society.

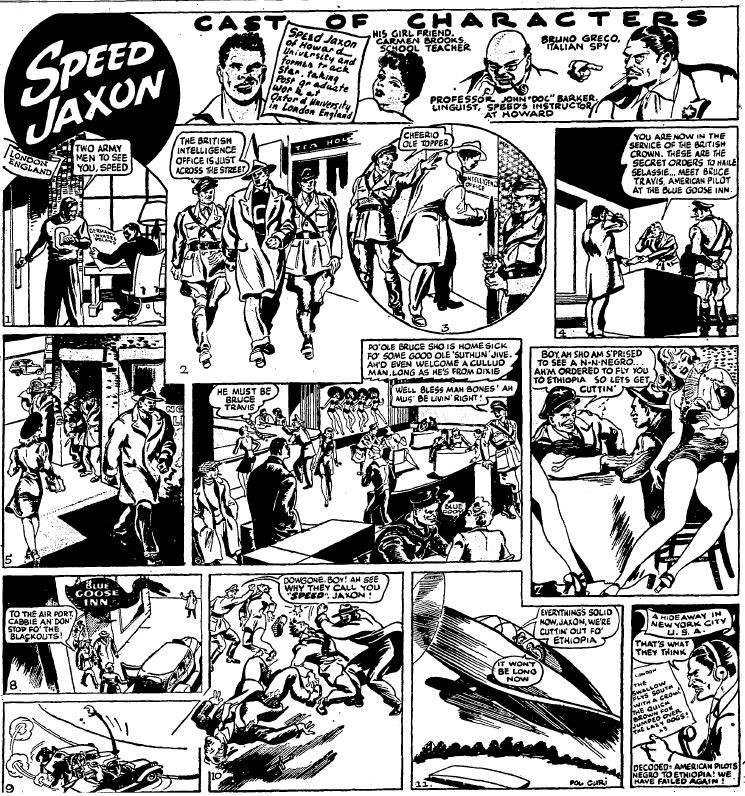

Bungleton Green expanded to 12 panels and a second 12-panel strip, Speed Jaxon, by Jackson under the pseudonym Pol Curi. The two filled most of the page. “Speed” is a former track star at Howard University. A giant of a man, better with his fists than Jackson ever was, he would beat up lots of fascists and saboteurs during the war.

Bung was small, but Speed was huge. Earlier his size had been no more than a comic effect, like Barney Google, Snuffy Smith, or Jeff of Mutt and Jeff. As realism seeped into the strips bones, he was known as a dwarf in the future. He’s no longer a layabout but an intelligent and respected member of the community. The new Bungleton Green’s first appearance shows him opening a teen community center called The Rumpus Room. In this scene, he gives teens left unsupervised, as their parents were off to war or at work all day, a place to go for wholesome fun.

The bad kids aren’t having any of it. Bung creates the Mystic Commandos, a gang of good black kids who will not only stand up against the black gang bullies but make decent citizens and patriots of them. Each week featured a new “secret password” for the Commandos. Always the name of a “Negro Hero,” the password was explained in a trailer panel that could be cut out and scrapbooked. The first hero honored was Booker T. Washington. The second was Prince Whipple. Prince Whipple was also a real historical figure, born in Africa and sold to and later emancipated by General William Whipple of New Hampshire. (The exalted nickname of Prince was sardonically bestowed on some newly-arrived African slaves.) Emanuel Leutze’s “Washington Crossing the Delaware” depicted a black oarsman. Legend had it that the figure was Prince Whipple. This is almost impossible from what we know of Whipple’s movements. However, Jackson understood propaganda as well as anyone in Washington.

Check out Part 2 of our special series, Jay Jackson and the First Black Superhero, tomorrow in the Chicago Defender.

For more on Steve Carper, visit his websites at www.flyingcarsandfoodpills.com or www.robotsinamericanpopularculture.com.