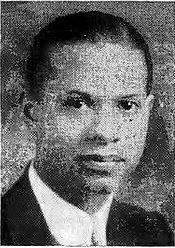

Steve Carper is a historian of popular culture. He researched Jay Jackson and compiled a unique commentary on Bungleton Green. The commentary uses illustrations from Jay Jackson, originally published in the Chicago Defender. January 6 was the superhero’s 76th birthday. In recognition, the Chicago Defender is pleased to feature the finale in our series, “Jay Jackson and The First Black Superhero” by Steve Carper.

THE FIRST BLACK SUPERHERO…Finale

Below, for the first time anywhere, the complete ten-episode run of Bungleton Green himself in the 21st century.

Figure 13: Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos in the 21st Century, November 25, 1944

Figure 14: Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos in the 21st Century, December 2, 1944

Figure 14: Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos in the 21st Century, December 2, 1944

Figure 15: Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos in the 21st Century, December 9, 1944

Figure 15: Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos in the 21st Century, December 9, 1944

Figure 16: Bungleton Green in the 21st Century, December 16, 1944

Figure 16: Bungleton Green in the 21st Century, December 16, 1944

Figure 17: Bungleton Green in the 21st Century, December 23, 1944

Figure 17: Bungleton Green in the 21st Century, December 23, 1944

Figure 18: Bungleton Green in the 21st Century, December 30, 1944

Figure 18: Bungleton Green in the 21st Century, December 30, 1944

Figure 19: Bungleton Green in the 21st Century, January 6, 1945

Figure 19: Bungleton Green in the 21st Century, January 6, 1945

Figure 20: Bungleton Green in the Twenty-First Century, January 13, 1945

Figure 20: Bungleton Green in the Twenty-First Century, January 13, 1945

Figure 21: Bungleton Green in the Twenty-First Century, January 20, 1945

Figure 21: Bungleton Green in the Twenty-First Century, January 20, 1945

Figure 22: Bungleton Green, January 27, 1945

Figure 22: Bungleton Green, January 27, 1945

The last strip set in the future ran on January 27, 1945. On February 3 Bungleton – now shortened to Bun instead of Bung – and Boo land in 1945 Memphis. (Logically, they should have been returned to 1943 a minute after he left, but that type of complexity was almost never allowed in time travel comic strips. Too confusing for audiences: it’s hard to comment on the here and now when your characters are living two years in the past.) However, Jackson sent Bun and Boo north to Chicago. Back in August 1942, remember, Bung officially and literally died in a Nazi prison. That news had been reported home, while his adventures in time were known to no one in the 20th century. Beebe, like many war widows, reformulated her shattered life and remarried. When a gigantic stranger rushes into his old house, he startles a happily married couple. Bun sees that he is the interloper and leaves. To commit suicide. Even SuperBun doesn’t realize just how invulnerable he has become. Neither a train nor a fall from a bridge break a bone.

Figure 23: Bungleton Green, April 21, 1945

Figure 23: Bungleton Green, April 21, 1945

In yet another odd twist to segue into a new plotline, the police who find Bun use the technicality that attempted suicide is illegal to blackmail Bun into being an undercover agent for them, infiltrating a local mob. After disposing of the small fry, Bun is confronted with the far more insidious S. Lippery Eel, a villain’s name worthy of Dick Tracy, whose racket is the very real-world white-collar crime of preventing black families increasingly overcrowded into South Side Chicago – Bronzeville – from moving into white neighborhoods, a scandal heavily fought in the editorial pages of the Defender. Eel is not subtle. “We want them burned out, bombed out, scared out! We want them out, see? And back across the tracks where they belong!” His moll, Proxie, is equally callous when she tells a dumb hood to “put on some brown make up and man-handle an ofay chic [sic]. The newspapers will arouse the dumb crackers and the tough negroes. You’ll have your excuse to put the blacks out, Mr. Eel.” The white papers “never mention the racial identity of any but negroes in a crime case!” Bun realizes.

Figure 25: Bungleton Green, October 13, 1945

Figure 25: Bungleton Green, October 13, 1945

After riots break out between blacks and whites, Bun has had enough. He drops through a skylight into Eel’s headquarters and singlehandedly lays out Eel and his henchmen. The official charge again them is starting a race riot, but, Bun says bitterly, they were “helped by professional race haters in Congress and some newspapers and real estate boards!”

Figure 26: Bungleton Green, November 17, 1945

Figure 26: Bungleton Green, November 17, 1945

The next set of adventures involves Eel’s chauffeur, Little Hat, who steals thousands of dollars of Eel’s stored cash. Little Hat is himself black but as crooked as the others. He runs a shoe shine parlor that is really a front for bookies and numbers runners, who prey on the black community by taking money they can’t spare. Jackson is not shy about mentioning the evictions, poverty, and broken marriages the pursuit of “something for nothing” resulted in.

Figure 27: Bungleton Green, February 16, 1946

Figure 27: Bungleton Green, February 16, 1946

Complicating the plotline is Eel’s white accountant, Doola, who blackmails Little Hat, who by then wants to quit the rackets, into becoming his partner. Doola is far the worse of the two: in swift succession he is shown committing two murders. Escaping from jail, he hides out as a black man passing as white, a perfect disguise that both shields him yet allows him complete freedom in 1946. He’s identifiable by a birthmark, though, and when Bun finds him, he allows Little Hat the honors of beating Doola to a pulp.

Bun and Boo take a much-needed vacation, but can’t escape crime. Bun finally displays some of his long-ignored superpowers when he interferes in a fight between the battling crooked couple Horseface and Sad Awhile and shrugs off a murderous blow to the head by a golf club as if it were a mosquito bite.

Figure 29: Bungleton Green, October 5, 1946

Figure 29: Bungleton Green, October 5, 1946

Jackson had created such a powerful figure in his revamped Bungleton Green that he himself apparently lost sight of his making Bun an actual superman and worried that his readers had also. He took the extraordinary step of having a character supply the meta-exposition. “I had almost forgotten about the super strength those scientists gave Bun in the twentyfifth [sic] century,” he has Boo say. Now that he remembered, he started to feature Bun’s powers in almost every week’s strip, creating a new adventure far more satisfying than “tracking down petty thieves!”

Figure 30: Bungleton Green, November 23, 1946

Figure 30: Bungleton Green, November 23, 1946

Bun and Boo set off for a dystopian South of such horrors that the green continent is made to seem like a mild inconvenience by comparison. Every strip reveals a new humiliation that blacks in the South have to endure every day and another set of irredeemable bigots. A few decent whites could be found to give hope for the future, although Northern “liberals” are depicted as condescending and clueless until Bun straightens them out.

Figure 31: Bungleton Green, December 14, 1946

Figure 31: Bungleton Green, December 14, 1946

Figure 32: Bungleton Green, January 18, 1947

Figure 32: Bungleton Green, January 18, 1947

Jackson again reprises scenes from the dystopian 21st century and sets them in the contemporary south: an attempt to get a cab turns out to be as futile as on the green continent, the “colored” hotel is “acrost the tracks,” the hatred and hypocrisy everywhere.

Figure 33: Bungleton Green, February 1, 1947

Figure 33: Bungleton Green, February 1, 1947

Figure 34: Bungleton Green, February 15, 1947

Figure 34: Bungleton Green, February 15, 1947

Figure 35: Bungleton Green, March 22, 1947

Figure 35: Bungleton Green, March 22, 1947

The invulnerable Bun can shrug off the dangers, but the strip makes clear that the ordinary black dweller in the South had to face and endure them every day with no help from superpowers. Even his true superpower often seems to be his incredible self-control and moral suasion in the face of truly evil enemies out to prove Langston Hughes wrong when he argued in the Defender in 1942 that his “colored people” should wholeheartedly back the war because “Although Alabama is bad, the Axis is worse.” (The quote comes from a special “Victory Through Unity” edition filled with a multiracial cast of notables including President and Mrs. Roosevelt, meant to assuage government fears that the “colored people” were too oppressed to cooperate with the war effort. Jackson drew the cover for it.)

Figure 36: Chicago Defender “Victory through Unity” cover, September 26, 1942

Figure 36: Chicago Defender “Victory through Unity” cover, September 26, 1942

Yet, as Bun says in the March 17, 1945 strip, “Yes, tolerance and understanding are necessary on both sides! The more we learn of each others’ problems, the less we’ll hate each other!” Education, cultural contact, and empathy would win in the end.

Unfortunately, on February 22, 1947, the strip shrunk back to its original four panel length, an almost impossible format to develop action and plot in a weekly adventure saga. Why this happened is not clear, so we don’t know whether Jackson was busy with other work or the shrinkage was an editorial demand. Sending Bun and Boo back to Chicago, Jackson plotted out an ending to his time travel saga. The May 17 strip shows Boo’s brother Targ appearing in Chicago bent on returning her to the 21st century. Bung almost decides that life in the future is better than hopeless struggle in contemporary America. Boo won’t give up the fight, though, and Bung stands with her. To no avail. Targ uses a “proton pistol” on him, not merely taking away his superpowers but telling him – in another astoundingly meta moment – that he would become again the “pathetic, little comic strip character” he had been.

Figure 37: Bungleton Green, June 7, 1947

Figure 37: Bungleton Green, June 7, 1947

Figure 38: Bungleton Green, June 14, 1947

Figure 38: Bungleton Green, June 14, 1947

Although the strip stumbles on for a few more weeks, on September 27, 1947, Jackson makes good his threat. Bung wakes up as the goofy-looking comic strip gagster he had been for decades. It has all been a dream. (Though he awakens in 1947, not 1943, and to 1947’s cast of characters. Comics must be consistent in their unreality.) As uninterested in a weekly gag strip as he was in the 1930s, Jackson turned over the strip to staff artist Jack Chancellor.

Figure 39: Bungleton Green, September 27, 1947

Figure 39: Bungleton Green, September 27, 1947

Bung would live on for almost two decades without achieving the recognition of these glory years. Jackson continued as the staff cartoonist for the Defender and freelanced for almost all the major black magazines of his era. A promotional campaign he drew for Pepsi-Cola that appeared in Ebony magazine made history for its normalization of the black image. In one 1948 ad, a well-dressed father and daughter see a pre-Warholish painting of a bottle of Pepsi hanging in a museum. The girl exclaims, “Mmm, Daddy! Now that’s art!” The dignity of the setting inverted all contemporary notions about black Americans. Even better, it served as a refutation of the company’s casually racist earlier ads. Four years before Pepsi had still been using grass-skirted natives with big lips to extol its product.

Jay Jackson moved to California in 1949, where he stayed except for a stint doing murals in Mexico, a nice flashback to his work for the world’s fair. He became an illustrator for the Telecomics Corporation, an early attempt at creating cartoons for television, although only still images with a narrator were used. Recognition came via two “Front Page” awards from the American Newspaper Guild, one for “his skewering of HUAC’s attack on Hollywood,” wrote Stephanie Capparell, because Jackson “was known for his biting satire of racists and red-baiters.”

Jay Jackson worked at levels both high and low. A two-page montage appeared in Who’s Who in Colored America and he did illustrations for Who’s Who in the United Nations. As always, awards didn’t pay the rent, so he churned out “Glamour Girls” postcards for Boston’s Colourpicture Publishers. He similarly planned two cartoon strips for syndication in the early 1950s, Girligags, with more pin-up style women, and Home Folks, a large single-panel strip featuring a realistic slice of life of the American black experience. Neither sold and Jackson’s life got cut short by a sudden heart attack on May 16, 1954. His widow managed to persuade the Defender to publish the two strips posthumously, and they were also syndicated to other major black newspapers, including the Michigan Chronicle, Louisville Defender, the Tri-State Defender and the New York Age Defender. Home Folks is “a masterpiece,” said Daniel Schulman, the exhibition curator for “African American Designers in Chicago: Art, Commerce and the Politics of Race,” a 2018 show at the Chicago Cultural Center. “It shows young, middle-class African Americans in a wonderful mid-century modern interior talking about how expensive things are, the dream of prosperity that was commonplace as a selling technique in the 1950s, this mass consumer market and postwar prosperity. In popular media, you don’t always see African Americans taking part of a stream of plenty in the 1950s.”

Jay Jackson’s style, a mixture of pride, anger, education, conciliation, and conflict, prefigures the varied and sometimes contradictory approaches to civil rights battles that would be fought after the war as leaders worked through the impossible quandary of determining how to reverse 350 years of American racism and racist policies. His approach, using humor and satire to ridicule the obvious political insanities and inanities of his contemporary world, was as powerful and effective as that of the social commentary of more famous comic strips like Barnaby and Pogo. His characterization of Bungleton Green as the Platonic ideal of righteous humanity also prefigured the way mainstream superheroes like Batman and Superman were handled in the late 1940s and 1950s and is nearly identical to the portrayal of the Black Panther when the character became the first black superhero in mainstream comics.

What deserves to be better recognized is Bungleton Green’s priority: he is the first back superhero in comic strips or comic books, preceding even Lion Man, who appeared in the single, June 1947, issue of All-Negro Comics. His brilliant idea of using science fiction to comment on racial issues also re-emerged, as with Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, which to great acclaim takes its slave-era heroine through a series of alternate worlds, each with their own horrors. Though the battle against officially-sanctioned Jim Crow is over, virtually all the issues Jackson tackled in his imaginary 21st century remain to blot our real 2020. 2043 is fast approaching. We should expect and demand that 2043 see a utopian and egalitarian America as fervently as Jay Jackson did.

For more on Steve Carper, visit his websites at www.flyingcarsandfoodpills.com or www.robotsinamericanpopularculture.com.