Jeffrey L. Littlejohn

by Jeffrey L. Littlejohn, Sam Houston State University

As a historian and director of the Lynching in Texas project, which has documented more than 600 racial terror lynchings, I receive regular emails from journalists, scholars and activists who want to discuss the history of racial violence.

My conversations with reporters and historians did not prepare me for one of the emails I received last winter. The writer, a Chicago memorabilia dealer, offered to mail me a photo album that included a picture from a Texas lynching.

I responded that I would appreciate the opportunity to review the album and to help identify the victim.

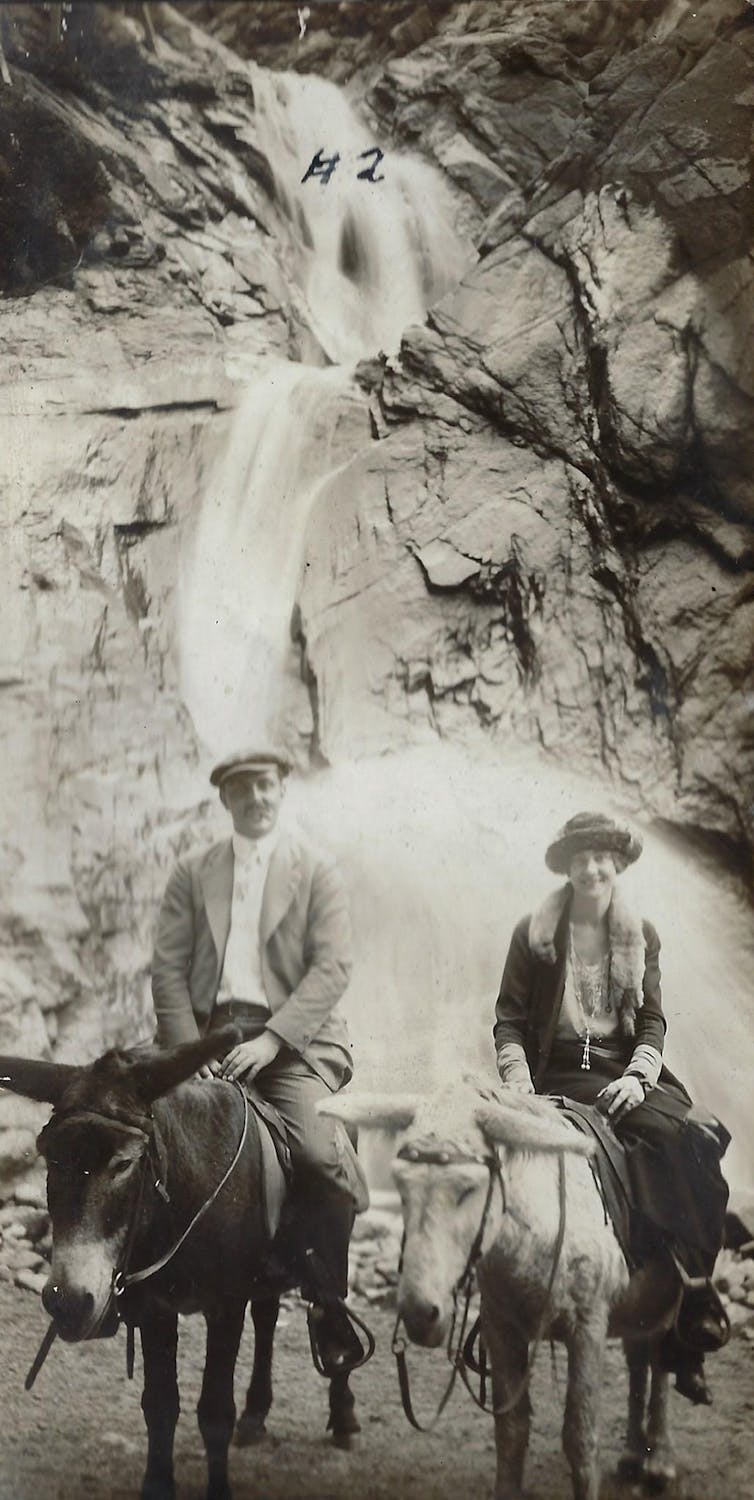

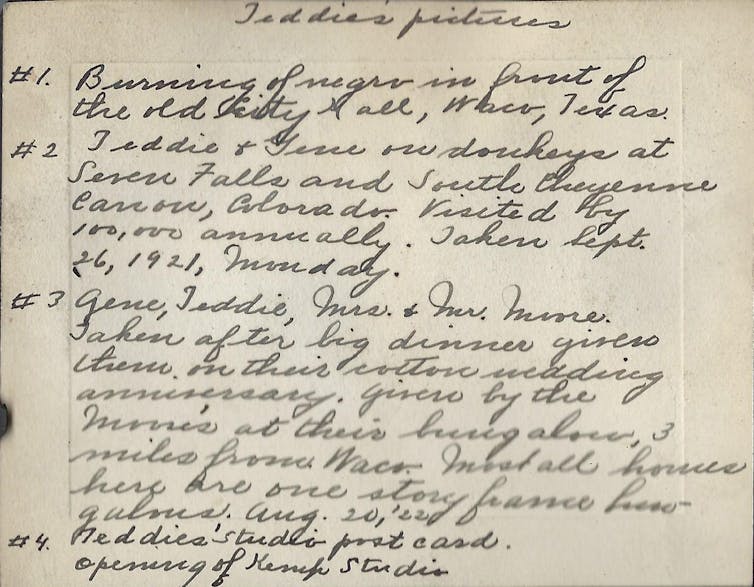

About a week later, I opened the envelope and found five photos, a small cartoon and a key labeled “Teddie’s pictures.”

Each of the photographs was numbered.

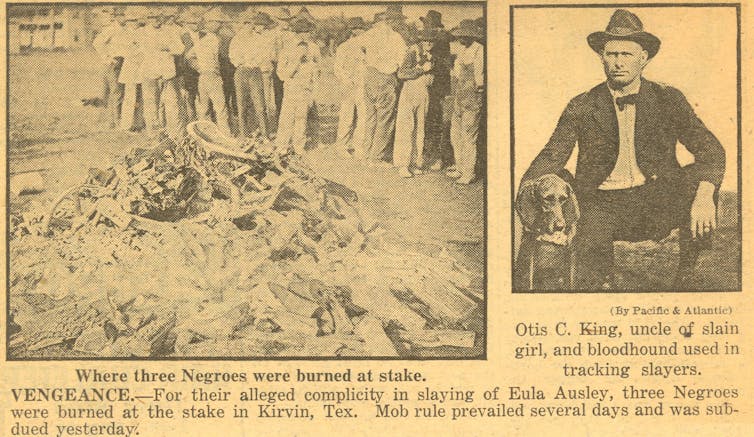

The first was a 6-by-5-inch image of what appeared to be burning wood. It proved difficult to decipher. But the description clarified matters.

It read: “Burning of negro in front of old City Hall, Waco, Texas.”

Revealing history lessons

I immediately set out to identify the victim and to discover the story behind “Teddie’s pictures.”

As I did so, I realized that what I was doing would be controversial, if not illegal, had I been a K-12 teacher in Texas.

In fact, I was engaging in the very kind of historical analysis that Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and Republican legislators in Texas want to ban from public schools.

In 2021, for example, Texas Republicans enacted Senate Bill 3 to prohibit K-12 educators from teaching that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from … the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.”

In other words, this official state interpretation holds that slavery, racism and racism’s deadly manifestation, lynching, did not serve as systemic forces that shaped Texas history but were instead aberrations without any fundamental meaning for Texans – or even beyond the state.

Teddie’s photo album, which also included pictures of Teddie and her husband doing normal, everyday things like riding donkeys and going to wedding anniversary dinners, presented a direct challenge to this interpretation.

Racist mob terror

Indeed, my research soon revealed that the pictures belonged to Mary “Teddie” Kemp, a white woman from Pennsylvania who moved with her husband, Gene Kemp, to Waco, Texas, in 1922.

This date proved crucial, because it meant that the victim in Teddie’s photo album could not be Jesse Washington, the 17-year-old mentally handicapped young man who was lynched in the infamous “Waco Horror” of 1916.

In that lynching, historian Patricia Bernstein writes, Washington was “beaten, stabbed, mutilated, hanged and burned to death on the Waco town square, before an audience of 10-15,000 screaming, cheering spectators.”

In fact, the dates on the other photos in Teddie’s album made it likely that this picture showed the burning of Jesse Thomas, a 23-year-old Black man.

Thomas was wrongly accused of murdering W. Harrell Bolton and assaulting his female companion, Margaret Hays, near Waco on May 25, 1922.

When Hays identified Thomas as her likely assailant, a relative named Sam Harris shot and killed Thomas.

A white mob then dragged his body to City Hall and burned it before a crowd of several thousand people.

White supremacy in Texas

The identification of Jesse Thomas as the victim in Teddie’s photo album only led to more questions.

Why would an educated white woman from Pennsylvania include a picture of a Black lynching victim in a personal photo album?

Why would she take her photos out of chronological sequence and place the lynching picture as the first photo in the album?

The answers to these questions reveal a great deal about Texas just 100 years ago.

In my view, the album exposes the priority that Anglo Texans – even new arrivals to the state – placed on white supremacy and Black subjugation.

Teddie likely pasted the picture of Jesse Thomas’ burning body at the beginning of her album because it featured an electrifying, adrenaline-charged event that viscerally illustrated the nature of her new Texas home.

Indeed, as historian William Carrigan has shown, white supremacy and racial violence served as core elements of the state’s identity.

Together, they established the written and unwritten rules governing the social order – who could vote, who could marry whom, who could attend events – and the ultimate punishment for transgressing the rules.

Lynchings, like the one depicted in Teddie’s photo album, present a direct challenge to the whitewashed view of Texas history that Abbott and his Republican colleagues prefer.

Unspeakable violence

Lynchings occurred regularly in Texas – with 16 in 1922 alone – and served as the most extreme and violent embodiment of white supremacy in the state during the Jim Crow period.

When Black and Hispanic Texans dared to challenge white authority or to claim for themselves the rights of U.S. citizens, they faced violence on a scale rarely seen in other parts of the country.

W.E.B. Du Bois Papers

In May 1922, for example, white Texans carried out in one month at least 10 lynchings, more lynchings than in any other state but Georgia for the entire year.

Eight of the Texas victims killed in 1922 were burned at the stake in a form of torture that most people today associate with the so-called Dark Ages.

But these horrific acts happened in modern Texas, just a few generations ago. And white people caught the events on film and put the photos in their own family albums.

One hundred years ago, the lynching of Black men and women in Texas was not an aberration. It proved the rule. You could say white supremacist rule.

Jeffrey L. Littlejohn, Professor of History, Sam Houston State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.