[ione_embed src=https://www.youtube.com/embed/jgXaUaTX8rg service=youtube width=640 height=360 type=iframe]

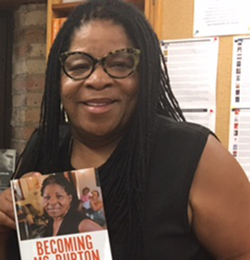

A diverse crowd of 20 eager Chicagoans surrounded Susan Burton, author of “Becoming Ms. Burton,” as she began an interview about her journey through abuse, repeated incarceration, recovery, and resilience in room 3 of Hyde Park’s Seminary Cooperative Bookstore. The group included a formerly incarcerated Ph.D. student, a trauma therapist, a university professor, a secondary school teacher, and a woman overseeing the health of female prisoners for the Department of Health and Human Services.

In addition to public appearances, Burton visits current or formerly incarcerated women at every stop of her press tour. Later, the author visited Chicago’s Metropolitan Correctional Center to speak with women who relate to Burton’s experiences within the criminal justice system.

Still suffering from the effects of sexual abuse in her childhood, Burton became addicted to drugs after an off-duty police officer’s car struck and killed her 5-year old son in 1982. For nearly twenty years after the incident, Burton cycled in and out of prison for drug-related nonviolent offenses. She never received therapy or treatment for her addiction. Eventually, however, treatment at a wealthy facility in Santa Monica, Calif., and the support of friends and family helped Burton break the cycle.

Burton then dedicated her life to giving the opportunity to regain full-fledged freedom after prison to other women. To start, Burton bought a house in Los Angeles and took a trip to the Skid Row bus stop where she was dropped off after each of her prison releases.

Burton looks back on that time fondly. “I knew where we got off the bus at and I’d stand there and I’d greet my friends, my community, my people, the women I did time with, and tell them about this house and ask them did they want to come live there. Sometimes they did; sometimes they didn’t. That was the real pioneer days. To have something to offer that would make a change felt really great,” she says.

Prior to the release of her memoir “Becoming Ms. Burton,” Burton was recognized as a Starbucks “Up-stander,” a CNN Top 10 Hero, and Soros Justice Fellow for her work as the founder and executive director of A New Way of Life, a nonprofit for formerly incarcerated women that provides reentry support through legal and financial services and a network of safe homes in south LA.

In California, it costs the taxpayers $75,000 to jail an individual for a year. Burton’s reentry program costs $18,000.

Burton sat down with the Defender to discuss her new book.

Becoming Ms. Burton is not a story that a lot of America has heard before. When you wrote this book about your life and activism, what audience did you have in mind?

This is a book for all of America, but it’s a book about a Black woman’s journey. For criminal justice classes; for the academic world; for social workers; for sociologists; and for women who find themselves in the shoes I was once in. I remember thinking, “Where is my life going to come together? Is my life ever going to count? Will I remain feeling so unappreciated both by myself and by others?” This book is for women who sit and wonder that. I want to give them hope to fight for their lives, to stand in our communities, and to not budge and not fall.

I want to give direction on how I was given the opportunity to make a better choice. Many times people don’t even understand that prison is not about a bad decision because people never had a choice.

Chapter introductions in the book include statistics about incarceration in America. You point out that it is estimated that as many as 94 percent of incarcerated women are survivors of physical or sexual abuse. Additionally, the lifetime likelihood of imprisonment for White women is one in 118; for Black women, it’s one in 19. How did you pick these statistics?

I wanted to tell a story about my life, but I wanted the story to be bigger than my life. This isn’t just happening to me. This is happening to all Black women and Black communities across our nation. The stats represent what I’m expressing through my life story on a larger scale.

As I was writing the book, I looked for stats about women. They were hard to find and I was like, “why?” Why is there no literature around women, specifically Black women, and mass incarceration? We know one in three Black men will be incarcerated, but one in how many Black women? It’s not out there. What is the effect on the community when that woman leaves? None of it has been researched.

Can you talk about some of the challenges mothers face in the prison system that you addressed in the book?

Women, once they’re incarcerated, are labeled as bad parents. Then their children are taken and they have to prove that they’re good parents. Proving that is like a full-time job–all of the classes and restrictions and requirements put on them in order to get their kid back. I think that it really parallels White people taking our children and selling them during slavery days. This child custody protective system is parallel to slave masters taking our children. Now it’s courts.

I can remember seeing this in the show “Roots.” That woman hollering, “massa, massa please don’t take my baby.” I watch these women in courts today with tears streaming down their eyes saying, “Judge, can I please have my baby back?”

Have any interactions or experiences during your press tour for the book really stood out to you so far?

In San Francisco, there was this woman who some people might have said disrupted the book reading. She was angry, really angry. I might say that she appeared to be someone who was actively using alcohol or drugs. Her son had just been given a whole bunch of years in prison and she just rambled and yelled about things that had happened in her life and we all just listened.

She reminded me of me—how angry and hurt I was prior to going to that place in Santa Monica. I thought about what she needed—access to service and a safe place to cry—and what she’d probably get. She’d probably get incarcerated so I didn’t question her.

One Black Woman’s Journey: A Real Criminal Justice Story