Blues lovers and history fanatics can sway to the smooth sound of saxophones, and the soulful voices of famous blues singers playing softly in the background, as they view the Chicago Blues Museum’s latest exhibition, “The Soul of Bronzeville.”

The exhibit tells its story, mainly of how music played a major role in the lives of African Americans in Chicago, through text, photographs, film and memorabilia from the museum’s archives. The set-up of the room encourages visitors to first learn about the Great Migration that more than 6 million Blacks made from the South to the North, Midwest and West between 1916 and 1970. And then from there, learn the role of the Black press, including the Chicago Defender, and of the city’s nightlife, record producing and radio stations.

This can all be seen at the University of Illinois-Chicago through Aug. 1. The exhibit is free and open to the public daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., in the African-American Cultural Center located on the second floor of UIC’s Addams Hall, 830 S. Halsted St. After-hours tours can be accommodated if scheduled in advance.

Lori D. Barcliff Baptista, director of the university’s African-American Cultural Center, said that many southerners brought their musical skills to the North during the Great Migration, which over time, became the Blues. Their skills were “honed” in Bronzeville, she told The Defender, because segregation kept them from performing at other venues.

“We had to start with some context about Bronzeville as a city within a city, and tell a little bit of the story of the Great Migration and how Chicago Blues was really created here, coming out of migrants [who] brought with them certain forms and styles, but really developed them here,” Baptista said.

UIC’s theme this year has been “migration and transformation,” so finding ways to look at different cultures and their diverse experiences was important, she added.

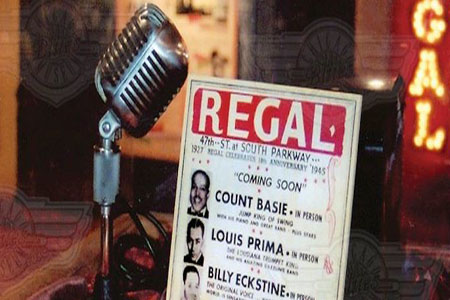

Patrons can expect to learn how nightclubs and the blues played a significant role in African-Americans’ lives. Newspaper articles and photographs of historical buildings like the Regal Theater, where entertainers like Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday and Ray Charles performed are spread throughout the open space.

Bronzeville was once home to famous clubs like club DeLisa (1935), which provided many up-and-coming Black entertainers a platform to get their name and talent out in front of the public. Photographs and a chronological timeline are available for visitors to view.

Longtime residents like eminent historian Timuel Black said the exhibition succeeded in capturing how music played a significant role in many African-Americans’ lives.

“I think in a very general sense, it does a very good job,” he said. “It tells the story of those in Chicago and what [music] meant to residents of the South side, in particular, those that were listeners and supporters of the Blues.”

Even though people were affected by the Great Depression, the music kept many souls lifted during the difficult time, Black said.

“Jazz, blues and gospel were part of that spiritual part of our lives; it gave [us] joy, hope and dreams,” he said.

But the exhibit isn’t just for students and faculty, Baptista said.

“Earlier in the planning process, when we decided we were going to work with the Chicago Blues Museum to present the exhibition here, I convened a meeting with folks from some of the major community organizations and institutions,” she said.

Some of those organizations included Centers for New Horizons, the Bronzeville Visitor Information Center and the Chicago Architecture Foundation.

Gregg Parker, founder and CEO of the Chicago Blues Museum declined to comment. Harold Lucas, 72, is the executive director at the Bronzeville Visitor Information Tourist Center and he said the exhibit might also bring more people to Bronzeville, which will help with tourism.

Lucas also said his organization supports the exhibition because it showcases what Blues was to African-Americans in the 1930s through the 1950s.

“Blues is music of that struggle of coming from the South to the North,” he said.

The music that developed in Chicago, also became the foundation for many other genres, such as jazz and gospel, Lucas said. “The style that formed in neighborhoods like Bronzeville eventually spread internationally. We had one of the wealthiest communities in the midst of the [Great] Depression.”