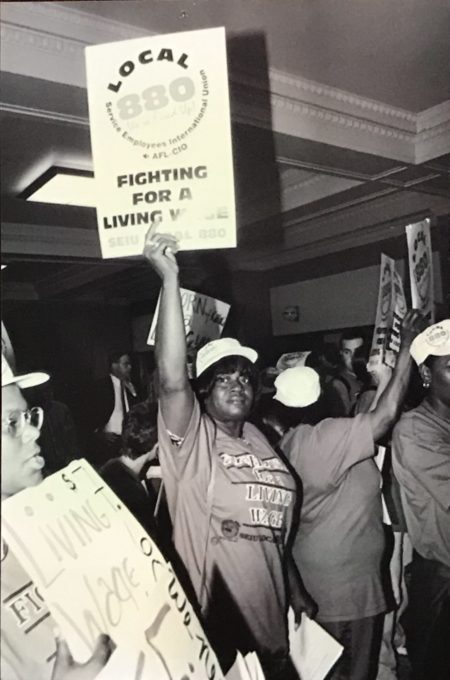

Ms. Petty, as a Chicago ACORN Board member, chairing a meeting with hundreds of ACORN and SEIU880 members from Chicago’s Black and Brown neighborhoods demanding that Citibank negotiate with Chicago ACORN and commit to a Lending Agreement. Utilizing the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) lending agreements like these negotiated by Lillie and the ACORN Banking committee led to tens of millions of dollars in new lending to Black and Brown families to build family wealth to those who had for so long been denied homeownership.

Photo: Courtesy of SEIU Local 880.

Ms. Petty, a Board member of Chicago ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now) and a founding member of United Labor Unions (ULU) Local 880, later known as the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 880, now known as SEIU Health Care Illinois, Indiana, Missouri and Kansas (HCIIMK), was active fighting for community and labor rights for the past 40 years. She passed away on February 22, 2022.

Ms. Lillie Petty was born April 17, 1945, in Batesville, Mississippi, to the union of Lee and Sallie Todd-Mitchell, who preceded her in death. Ms. Petty was the youngest of 11 children. She received her formal education in Panola County School District in the Mississippi Department of Education. After leaving her hometown of Batesville, Mississippi, she later moved to Chicago, Illinois, with her older siblings.

As a member and then Board member of Chicago ACORN, Ms. Petty was active in affordable housing, predatory lending, living wage, insurance redlining, and banking campaigns. She was an energetic member of the ACORN Banking committee that successfully challenged banks under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) over their poor lending records in Chicago’s Black and Brown communities and negotiated lending agreements with those institutions resulting in tens of millions of dollars in increased lending and hundreds of new homeowners, building family wealth for communities that had been denied resources for decades.

She initiated Chicago ACORN’s fight against insurance discrimination for Black customers, which grew to become a national campaign, bringing some of the largest home insurers in the nation to the bargaining table. In March 1993, Ms. Petty testified before Chicago Congresswoman Cardiss Collin’s Subcommittee in the United States House of Representatives on ACORN’s study showing that insurance companies like Allstate charged higher rates in Black neighborhoods.

Ms. Petty testified on her experience with Allstate raising her rates after she had signed the policy: “…I found that, to me, it is like a ‘bait and switch situation. They bait you in, and then, once you get in, they switch you for something else.” Congresswoman Collins evidently agreed to introduce legislation to correct some of the discriminatory policies. Ms. Petty concluded her testimony: “…We just want to be able to live. We want for the future. We don’t want to see this happen for our children – the abandoned buildings all around, and for our kids – when they come up they cannot even get insurance. At the rate they are going, it is skyrocketing. After a while, no one will be able to afford a home like myself…”

Ms. Petty was a leader in the campaign against Avondale Federal Savings and Loan, using the Community Reinvestment Act to intervene with ACORN on Avondale’s poor lending record in Black communities, and negotiating a lending agreement with them in 1992. Ms. Petty and her husband worked for two years to save enough money for the down payment on their new home, which they purchased in 1992 and where they raised their grandchildren.

Photo: Courtesy of SEIU Local 880.

In 1984, Ms. Petty was working as a personal care attendant (PCA) for the Illinois Department of Rehabilitation Services (DORS), caring for homebound seniors with disabilities, earning only $3.35 an hour, the minimum wage at the time, while others earned as little as $1 per hour with no benefits. When a union organizer knocked at her door, she immediately joined the union – one of the first union members of Local 880, at the time a fledgling union with few members or resources. When told by the state that she and her coworkers were “independent contractors” and had no rights to minimum wage or other benefits, or a right to organize a union, she and her coworkers initiated a 20-year fight for living wages, benefits, and job security – marching on the state capitol in Springfield, lobbying, engaging in direct action and finally culminating in the passage of collective bargaining legislation by the Illinois General Assembly for homecare workers in 2003 and winning their first union contract containing living wages, benefits and many other improvements.

Today, because of leaders like Ms. Petty, those same workers now earn $16 per hour and will earn over $17 an hour by the end of 2022, they have fully paid healthcare, paid training, and coverage under Social Security, unemployment, and other benefits they never had.

Her union local, once known as the smallest local union in Chicago, is now the largest union in the city of Chicago, in the state of Illinois, and in the Midwest representing over 92,000 homecare, childcare, nursing home, hospital, and other healthcare workers.

Ms. Petty lived a full life.

Ms. Petty’s husband, Mr. Elbert-Ralph Petty, preceded her in death. She was also preceded in death by her parents; seven brothers, Preston Adair, Russell Adair, Bishop William Doris Adair, Joseph Mitchell, J.W. Mitchell, Cleveland Mitchell; two sisters, Katherine Dunning; Mattie Holmes-Betts.

Ms. Petty leaves to cherish her loving memory: Sons; Reginald Mitchell, Darnell Mitchell; Daughters; Sherri Mitchell, who precedes her in death; Bridget Mitchell, Angelica Walker, Chrisha Mitchell; 7 Grandchildren; 4 Great-grandchildren; and a host of nieces, nephews, and friends.