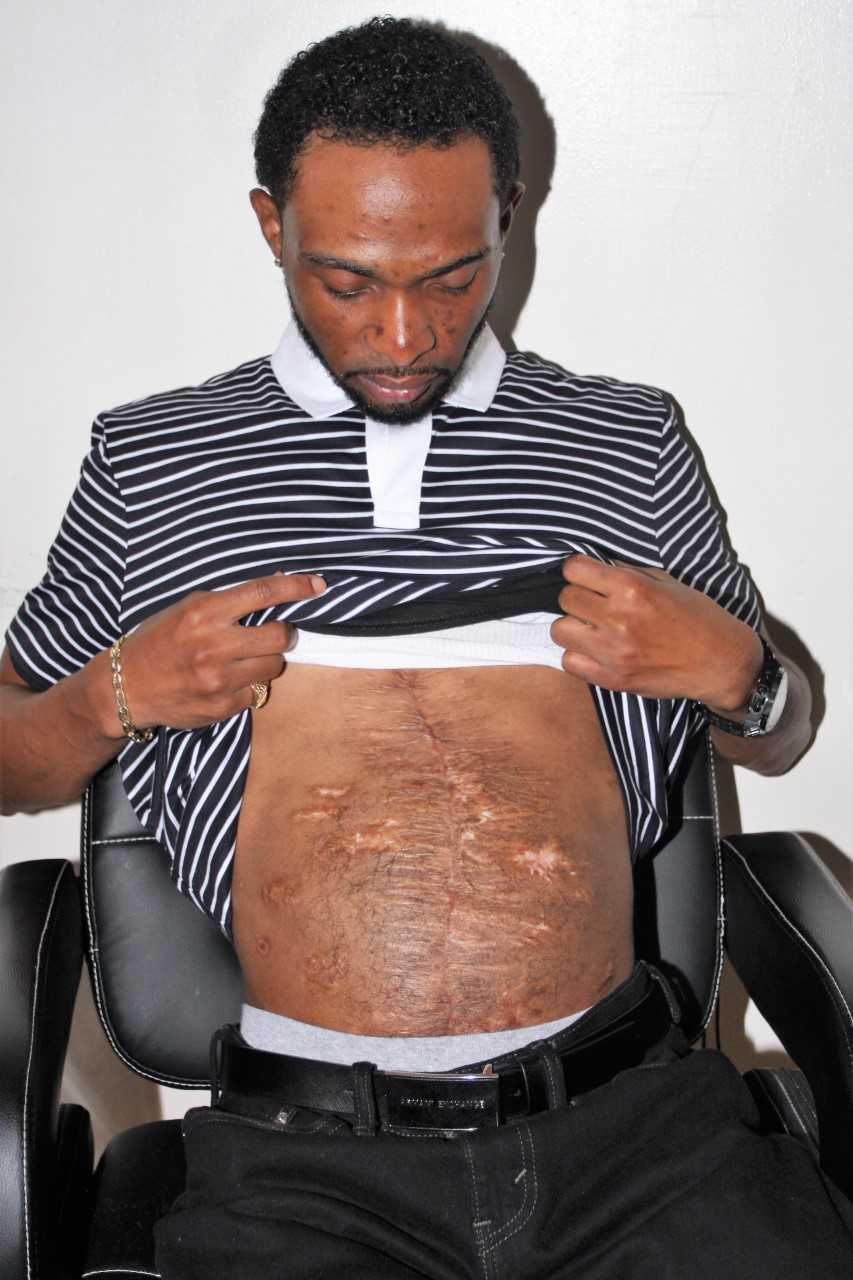

Patrick Noel shows his wound from gun shots; picture by Malrie Sonier

With gun violence occurring so often and in such high numbers in Chicago, you seldom hear about the struggles and challenges survivors face as they try to regain some semblance of a life that has forever changed.

An estimated 80,000 people survive nonfatal gun injuries in the U.S. each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Chicago resident Patrick Noel is one of the survivors still healing from his wounds.

It was a late evening in July 2016 when Noel returned home after spending time at a backyard cookout with his twin brother Derrick Noel and other friends and family on Chicago’s South Side when two men he didn’t know drove up and opened fire, hitting him six times in front of his Calumet City home.

That year, Chicago made national headlines that read, “Chicago saw more homicides than New York and LA combined,” that prompted then President-elect Donald Trump to tell Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel to seek federal help to deal with the City’s most violent year in two decades that saw 762 homicides, 3,550 shooting incidents and 4,331 shooting victims, 1,100 more shooting incidents than 2015, according to Chicago Police Department data. In comparison, this year, there have been 374 homicides with 1666 people shot and wounded, according to statistics at heyjackass.com. At press time, 41 of those homicides occurred in August 2018.

We often hear of the grief of the loved ones left to mourn those who have been killed, but there’s another tragic picture: the victim left to live with the lasting impact of the violence—physically and emotionally.

Noel is still healing from the 37 surgeries it’s taken to repair his leg and the damage done to his mid-section, including the implantation of seven feet of intestine donated by his twin brother Derrick Noel. He’s also learning to walk with the rod in his left leg, all part of the new way of living he’s still adjusting to as a survivor of gun violence.

“I don’t remember feeling the pain after being shot,” Patrick Noel said during an interview with the Chicago Defender. “It had to be mistaken identity because I didn’t know them. I went to work every day, kept to myself and spent my time with my son. They [shooters] were about 10 feet away from me and asked if I lived there. I hesitated but said yes. I felt the force of a bullet hit me in my left leg and I fell to the ground. They shot ten times, I was hit six times. I remember yelling for help. I remember seeing a neighbor from across the street. Someone called my brother. My mother said I was talking and conscious but I don’t remember. I was also hit in the foot, my shoulder, abdomen, my backside and a bullet grazed the back of my head.”

Noel was taken straight into surgery at Advocate Christ Hospital. The bullet broke and shattered the bone in his left leg.

“I have a rod that runs from my knee to my hip and I walk with a slight limp and still have bullet fragments that are still coming out.”

Physical recovery from a gunshot, even if someone is only grazed, can take months to years with psychological consequences that can last a lifetime, experts say.

In addition to the injury to his leg, Noel faced an even bigger challenge with the bullet that pierced the blood vessels supply to his small intestine causing the organ to start to die, according to Enrico Benedetti, professor and Warren H. Cole Chair of Surgery at the University of Illinois Hospital.

A renowned transplant surgeon, Benedetti has performed approximately two-thirds of the world’s small bowel living donor transplants. He is also one of just four surgeons worldwide to perform an identical twin living-donor small bowel transplant. Only four of these surgeries have been performed worldwide.

Noel ended up at the UI hospital thanks to his sister who called around in search of a doctor to perform his abdominal surgery while he was at Advocate Christ. A doctor at Advocate was also trying to reach Benedetti at the same time.

Noel’s abdominal area remained open for six or seven months, so the doctors and nurses could clean it. He received nutrition intravenously.

“They covered it with mesh,” Noel said. “I wasn’t able to eat regular food. I was in a lot of pain and lost a lot of weight.”

Doctors at UI Health told Noel he would more than likely require a small bowel transplant. The small bowel, also known as the small intestine, is responsible for absorbing nutrients from food. If it’s damaged or removed, patients have to receive nutrition intravenously, which carries risks of line infections and liver failure.

Noel had a perfect match for a transplant in his identical twin brother, Derrick, who did not hesitate to help his twin.

“Words can’t describe what I felt when I first saw my brother on the hospital stretcher right after he was shot,” Derrick said. “He had just left my house and had just talked to a friend of ours on the phone right before he was shot.”

Though Derrick, who works as a barber in an area where gun violence is prevalent, has healed physically from the surgery, mentally and emotionally it was rough for him and he said he has trouble sleeping. He recognizes that he and his brother were traumatized and is open to counseling.

He added, “some of my young clients [at the barbershop] survive the gun violence and some don’t.” He thanked Dr. Benedetti and the other doctors and staff for saving his brother’s life.

The Noel twins had the transplant surgery in 2017.

A Perfect Match

“When I learned that Patrick had an identical twin willing to make the donation, I knew that a living-donor transplant would not only be possible, but because his brother is a genetic match, he is also a perfect match,” Benedetti said. “Rejection and infection are the two main concerns for any transplant, especially opportunistic infections that arise due to the immune-suppressing anti-rejection drugs. Because of Derrick, Patrick effectively avoids both these risks.”

Benedetti and Ivo Tzvetanov, associate professor of transplant surgery in the UIC College of Medicine, removed about seven feet of the small intestine from Derrick — most people have about 20 feet of small intestine — and used it to connect Patrick’s stomach and large bowel. The surgery went smoothly and both brothers had a rapid recovery, though Patrick is still healing.

Noel’s insurance initially did not want to approve his surgeries, but eventually covered it he said thanks to his sister and UI health who worked to get it approved.

Life Changes

As he continues to heal and adjusts to a life that was forever changed by the shooting, Noel lost the longtime job he held prior to the shooting because of the length of time he was off. The job also requires heavy lifting, something he’s not able to do anymore.

“I worked my way up to being a supervisor but it was a physical job,” Patrick said. “I can’t do the things I used to do like sitting up and tying my shoes. They couldn’t stretch my abdominal muscles back together because I was opened and closed so many times. I have a lot of scars from being cut for tubes and air pockets and the surgeries. I have to roll out of bed and I can’t run and play with my son. My son, who was six when I was shot, went swimming over the summer but I couldn’t swim with him. I didn’t tell him I was shot until last year. I can’t even lift him and wrestle with him. I was also into home improvement but can’t do that anymore. My son helped me a lot when I got home after spending ten months in the hospital. I have a lot of scars.”

As he heals, Noel acknowledges the mental trauma he’s suffered but said he doesn’t have nightmares.

He’s starting on the path of becoming a motivational speaker so he can share his story. He’s also in the beginning stages of starting a nonprofit organization.

He says that his family was a great support for him and that he loves them very much.

As for the gun violence, he said young people are being misguided and the lack of resources in high crime areas and the lack of parenting need to be addressed.

“I moved from Calumet City and also thought about moving out of Chicago, but I’m going to stay and offer help and try to change things,” Patrick said.

Help for Victims

Pastor Donovan Price is a First Responder Pastor who shows up at the scene of shootings to console the victims’ family members and to also offers solace for the police and reporters on the scene.

Price has a bachelor’s degree in psychology and has studied Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He said it’s part of what happens with crime and is a result that flips into the cause of crime.

“A young man with anger feels he has to carry a gun because ‘they’ have guns and because he’s in danger just going back and forth to work or wherever he’s going,” Price said. Even in the midst of all the crime and PTSD, people still have to go to work and school, and so people just take their PTSD along with them wherever they have to go and are not getting treated for it.”

Lori Lightfoot, a Chicago mayoral candidate, said on WVON last week that gun violence should officially be deemed a public health crisis. If gun violence was deemed as such, the approach to dealing with it would be different. The efforts would be finding the root cause and how to treat it in a holistic way, she added.

Local activists are calling for more capital investment and more social resources in the high poverty, high crime areas of Chicago.

Attorney General Lisa Madigan’s office provides services to help victims meet their challenges and regain peace of mind. Programs administered by the Crime Victim Services Division include The Illinois Crime Victim Compensation Program, which provides direct financial assistance to innocent victims of violent crime to reimburse out-of-pocket expenses related to the crime.

For more information, call the Crime Victims Assistance Line, 1-800-228-3368 (Voice)

1-877-398-1130 (TTY).