Lindblom Math and Science Academy students Lea Starling, Jonathan Parnell, Everett Murrell and Jon Murphy never paid much attention to their old gym teacher, Greg Outlaw.

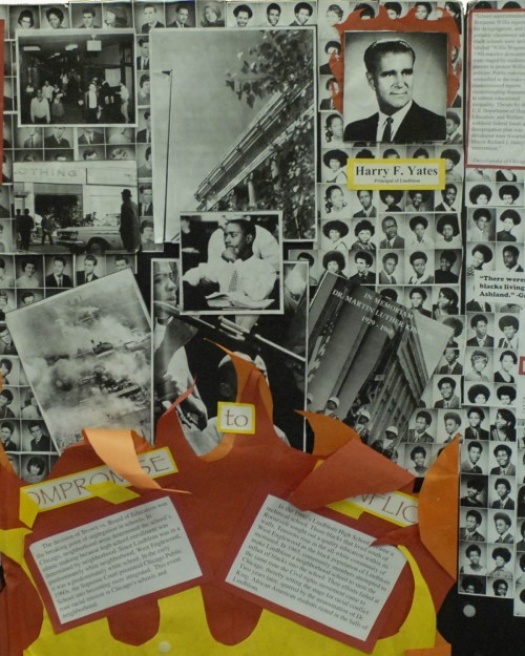

“When you ask him about one thing, he’ll go off talking about another,” Murphy laughed. But one day Outlaw trailed off into a monologue about the Lindblom riot of 1968 and the studentsûwho were interviewing him for a history assignmentûwere hooked. “He said there was a riot here, and all the teachers locked themselves in the art room to avoid being attacked. That made me want to do more research into what happened and what led up to it,” Starling said. The assignment became a year-long project that won an Outstanding Entry in African-American History award at the National History Day Finals in Maryland and sparked the memories of alumni who lived through that time. A decade after the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision, Lindblom was still a predominantly white school located in a predominantly white neighborhood, West Englewood. Then-Chicago Public Schools superintendent Benjamin Willis preferred to tack mobile units onto already overcrowded Black schools instead of allowing them to integrate. But a 1964 Hauser Report found CPS to have “gross racial imbalance,” and the government threatened to withdraw federal funds if the system did not right itself. Lindblom was forced to become a technical school in 1965, allowing students of any race to enter as long as they passed an entrance exam. But it was clear the Black students weren’t welcome, and as their population increased, community members lobbied for Lindblom to return to a neighborhood school. Outlaw, who was a Lindblom student at the time, recalled sprinting from the school to the bus stop to avoid the racial slurs hurled at him by West Englewood residents. “You can feel when you’re not wanted. I always said it’s like walking down the street in Selma, Alabama.” Outlaw said. The community’s efforts failed, and Lindblom stayed technical. But Black students’ anger came to a head when then-principal Harry Yates took three days to recognize Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s death after the civil rights leader was shot in April 1968. When Yates finally did call a school assembly, he dismissed the angst of his Black students, telling them they needed to calm down. The students walked out of the assembly, some smashing trophy cases on their way out. Fearful teachers locked themselves in an art room. “Mr. Outlaw said that during the riot they smashed the trophy case, and that’s why our trophy case is separated into two pieces now,” Murphy said. The event made local news and white flight ensued. Lindblom eventually became a predominantly Black magnet school. “Everyone moved out to the suburbs. Mr. Outlaw said that every day each desk was being emptied. Ten, 15 kids would transfer each day. So, within five years, 1968 to 1973, 1974, the school became predominantly Black, and they all left the neighborhood.” The students used old yearbooks, Chicago Tribune and Chicago Defender archives, old housing reports, community inventory surveys and interviews with Outlaw to piece the story together. And for them, it was a journey back in time that rivaled their greatest imaginations. “I’ve looked down the hallway and thought, “There was a riot in this hallway,” Starling said, a hint of wonder in her voice. “How could you go to class everyday where a teacher may be racist or the other 19 kids around you in that small little class are racist. It’s just amazing to me.” Leila Noelliste can be reached via e-mail at lnoelliste@chicagodefender.com. ______ Copyright 2008 Chicago Defender. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.