On what would have been renowned writer Gwendolyn Brooks’ 101st birthday, the City of Chicago received a special gift. On June 7, the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame unveiled a beautiful bronze statue in Brooks Park, 4542 S. Greenwood, to pay tribute to the woman who was the Illinois Poet Laureate for more than 30 years and the first Black person to receive a Pulitzer Prize.

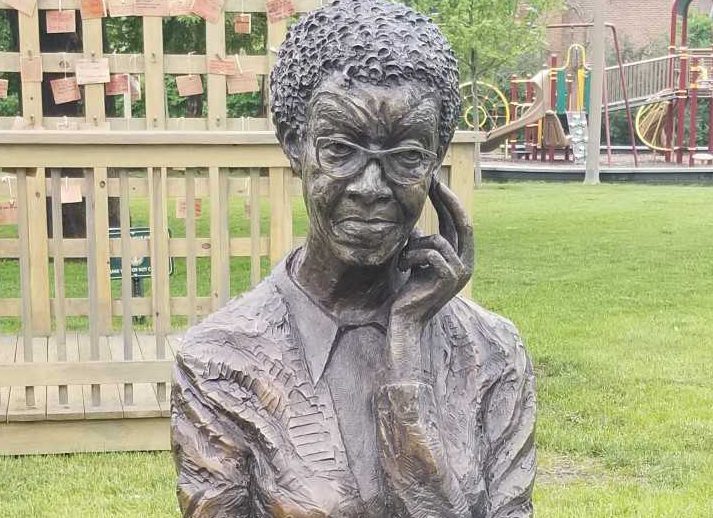

“People will know this wonderful poet we’ve had in Chicago all these years—101 years now—and understand more about her,” said Margot McMahon, the award-winning artist who created the sculpture. The tribute to Brooks includes a wooden porch, symbolizing where she often wrote as a young child, which invites visitors to pen their own haikus and post on the porch. There are also stepping stones along the path from the porch to the statue; the stones include quotes from Brooks’ work Annie Allen. Then, the statue is surrounded by large stones symbolizing Brooks’ ascension to one of the country’s best writers. The portrait itself symbolizes the teacher, mentor, editor, activist and inspirer she became.

“I wanted to give the viewer the opportunity to meet Miss Brooks,” McMahon wrote. “I wanted to sculpt her listening to us and giving importance to our stories, like she had for many school children.” I wanted to sculpt her humanism that encouraged us to be all we could be. Her listening to stories gave importance to each person. Her witnessing each story and forging stories into literature gave humanity new insights….I wanted Gwendolyn Brooks to be here for us, looking down, as witness, to our own efforts at making a positive impact, here in her old neighborhood, and everywhere else.”

Nora Brooks Blakely, Gwendolyn Brooks’ daughter, said moments before unveiling the sculpture that her mother was “not a crier.” She had only witnessed her mom shed tears a few times in her life, but she thought her mother would have been touched by the statue and would have shed a tear had she been alive on this historic day in Chicago.

During the ceremony prior to the unveiling, held at Kenwood United Church of Christ across the street from the park, Blakely along with other community members shared fond memories of Brooks and her contribution to the literary world.

“She loved words, listening and learning,” her daughter said. “She loved children, news…the idea of family, tea, jam, fried chicken, soap operas, socializing in her own way…giggling on early morning phone calls.”

Most of her Brooks’ work centered on Chicago, particularly Bronzeville. She was published at a young age in the Chicago Defender. Many of her poems were published in the paper’s “Lights and Shadows” section. Her first book of poems was A Street in Bronzeville, which was published in 1945. She went on to publish Annie Allen in 1950, which won her the Pulitzer. Her only narrative book, Maud Martha, was published in 1953. She taught at several colleges in Chicago and New York. She and her husband Henry Lewington Blakely, Jr. had two children: Henry III and Nora. Brooks died on December 3, 2000, in her Chicago home.

Brooks’ generosity, especially to young writers, was also highlighted at the unveiling ceremony. She funded poetry contests from her own pocket, recalled Mike Puican, a writer. She invited kids from all over Chicago to send in poems and she selected 30 students, published their work in a book and invited them to the University of Chicago, where she presented each student with a book and an “envelope of cash,” said Puican. She did this for 30 years.

Puican also said she funded a $500 prize for open mic contests. While he didn’t win one of her prizes, he did receive a personal note from her after he presented his work at one of the open mic contests. He said the note, which said “you are unique and splendid,” is now framed and hangs above his writing desk to this day.

Haki Madhubuti, author, publisher and former professor at Chicago State University (CSU), along with Kelly Norman Ellis of CSU, talked about working with Brooks and how much she gave of herself to others.

“Her religion was kindness,” said Madhubuti, who persuaded Brooks to come out of retirement to teach at CSU. He told her, ”One half of students [at CSU] are working class Black women…they need you…that got her.” She stayed for 10 years.

“Gwendolyn Brooks: The Oracle of Bronzeville” is positioned at the south end of the park on the Southside of Chicago, hopefully inspiring the young people who will run by on the way to swing and climb on the playground.

Gwendolyn Brooks: The Oracle of Bronzeville