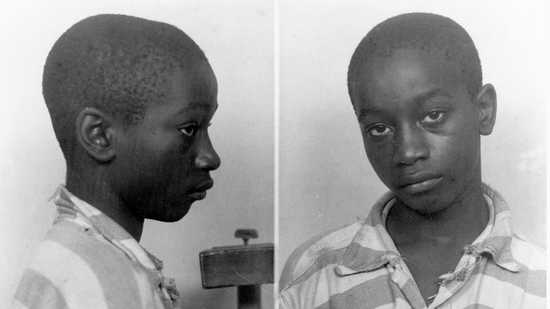

Carmen T. Mullen, a South Carolina state judge, recently vacated the conviction of George Stinney for the killing of two white girls, finding that the case was riddled with “fundamental, constitutional violations of due process.” She added: “it is highly likely that the Defendant was coerced into confessing to the crimes due to the power differential between his position as a fourteen-year-old black male apprehended and questioned by white, uniformed law enforcement in a small, segregated mill town in South Carolina.”

The judge’s action, however, did not do George Stinney one bit of good. He was executed by the state of South Carolina for that murder more than seventy years ago, at the age of fourteen. No one younger was executed during the twentieth century in the United States.

On the one hand, we can certainly say that what happened to George Stinney would not have happened today. The trial took place in a county where three out of every four people were black, yet Stinney’s jury was 100 percent white. The sole evidence of his confession was the say so of the local sheriff. Stinney was questioned without a lawyer present, and denied having confessed during his trial. His appointed attorney had never before represented any defendant in a criminal case, and during this trial —for capital murder—doesn’t appear to have done anything to defend his client. He asked no questions of the prosecution’s witnesses, and didn’t call a single defense witness. Three hours was the duration of the entire trial. The jury required all of ten minutes to convict and sentence George Stinney to die, and the state of South Carolina electrocuted him less than three months after his arrest.

Things would not have gone that way today, and we must give our thanks for that to those who fought, bled, and themselves died so that the laws of our land would finally—one hundred years after emancipation and the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment—treat black, white, and all Americans of every race the same. Yes, discrimination is now illegal, and no injustice as blatant as that which South Carolina visited on George Stinney would stand today. Progress is real. Yet, of course, our progress on the matter of American racism is not complete. Better, in the words of President Obama, is not good enough.

For more, go here.