NEW YORK — When gay rights leader Harvey Milk attended high school in suburban Long Island in the 1940s, and later taught math and history and coached basketball there, he kept his sexuality a well-guarded secret.

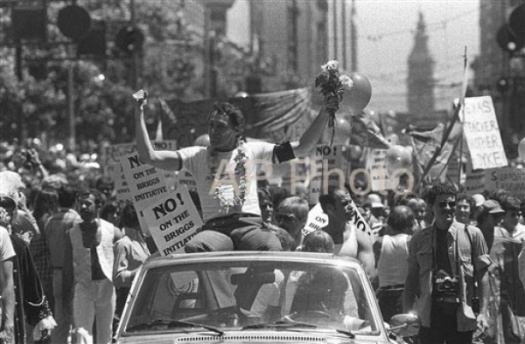

NEW YORK — When gay rights leader Harvey Milk attended high school in suburban Long Island in the 1940s, and later taught math and history and coached basketball there, he kept his sexuality a well-guarded secret. "Like most men of his generation," biographer Randy Shilts wrote in "The Mayor of Castro Street," ”Milk assiduously stuck to the double life he had carefully followed since his high school days." More than half a century later, the Long Island Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Services Network will honor the slain gay-rights activist posthumously to draw attention to gays and lesbians with small-town roots. Milk’s nephew, Stuart Milk, will accept the award for his uncle on Saturday. "Things have changed dramatically since the late 1940s when Harvey Milk graduated from high school," said David Kilmnick, founder of the network of three organizations. "But there’s a lot more to be done." Milk, the focus of renewed attention this year when the biographical film "Milk" won two Oscars, became one of the country’s first openly gay elected officials when he was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977. In November 1978, Milk and San Francisco Mayor George Moscone were fatally shot by Dan White, a disgruntled former city supervisor. Milk was 48. Since the days when Milk was growing up in the shadow of New York City, there’s no question life for gay men and women on Long Island, home to more than 2.8 million people, has improved in many ways. Many gays and lesbians say they feel comfortable enough to live openly. Still, they add, not everyone welcomes that openness. One of the goals of Kilmnick’s organization is to get suburban and rural gays and lesbians to live openly gay lives and create friendlier environments in their hometowns, rather than flock to gay meccas like New York, San Francisco and Atlanta. That was partly the point of the posthumous award to Milk, he said. "We need to keep some of that in suburban and rural America if we truly want to see full equality," Kilmnick said. When Milk was elected, he was only the fifth openly gay U.S. elected official, according to Denis Dison, a spokesman for the Gay & Lesbian Victory Fund, a political action committee. Today there are 427 openly gay elected officials, Dison said, and more than three-quarters of them serve at the local level. "In the last few years, there have been folks who did not leave their towns and go to the coastal cities," he said. When Kilmnick and his partner of eight years moved into their Long Island home in 2003, a neighbor dropped by to welcome them to the neighborhood. "She asked, ‘Oh, where’s your wife?’" Kilmnick said. He then introduced her to his male partner, Robert. "This was six years ago, and we haven’t seen her since," he said. Still, Kilmnick said, there’s tangible evidence things have changed since Milk lived in Long Island. There are 67 gay-straight alliances in Long Island schools, he said, and last year, more than 40,000 students participated in National Coming Out Day. ______ In photo: In this June 26, 1978 file photo, then San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk is seen in San Francisco’s seventh annual Gay Freedom parade. A network of Long Island gay and lesbian advocacy groups is honoring the slain gay rights activist this weekend. Milk grew up on Long Island and graduated from high school there in the late 1940s _ keeping his sexuality a well-guarded secret. Copyright 2009 Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.