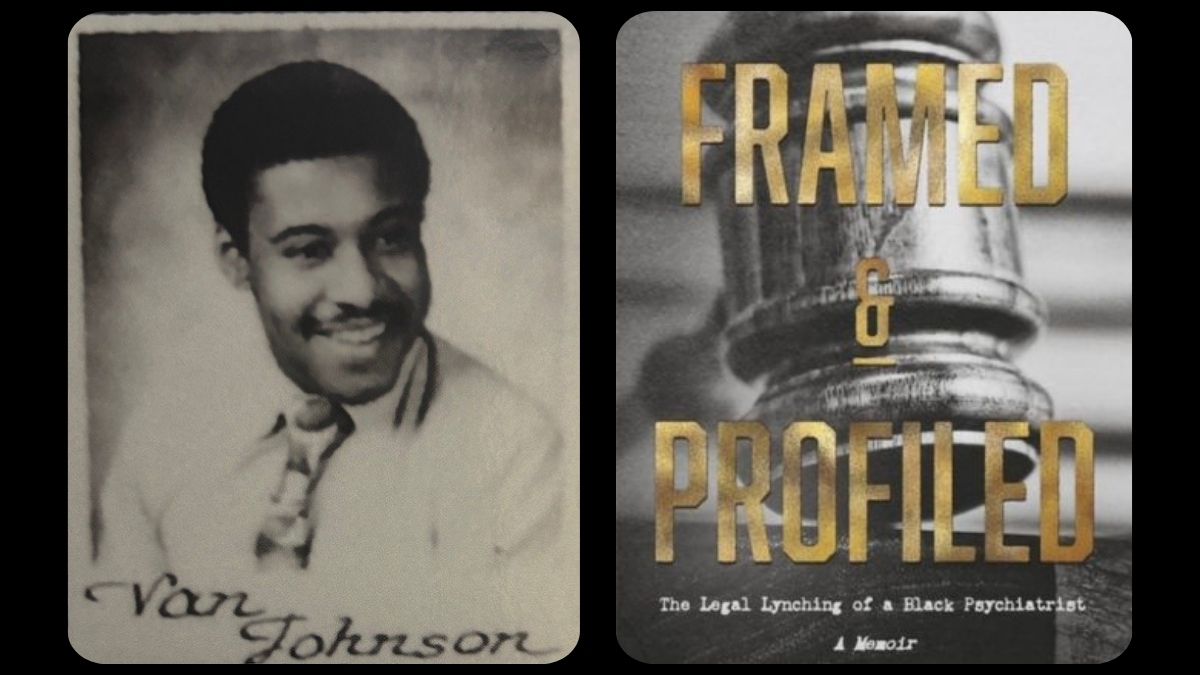

Van Johnson and the memoir that tells his tragic story, Framed and Profiled (Photo Provided).

BHM Our Ancestors: Honoring the Pioneers – Stories about our legends who paved the way.

“There is an old saying: ‘Truth is sometimes stranger than fiction.’ That phrase applies to my story, the first Black psychiatrist to open a practice in Anderson, Indiana. A lot of my white patients affectionately referred to this region as ‘Klan country’ or a Sundown town.”

This quote from Dr. Van Johnson’s memoir, “Framed & Profiled: The Legal Lynching of a Black Psychiatrist,” encapsulates the harsh realities he faced when his life was tragically derailed, revealing deep-seated injustices that would irrevocably alter his path.

A young Black psychiatrist and Harvard fellow from the South Side of Chicago, Dr. Johnson moved to Anderson, Indiana, in May 1989, lured by promises of opportunity and belonging. Yet beneath this inviting facade of small-town living lay a brewing storm of racial bias and systemic injustice that would ultimately lead to a legal lynching.

Dr. Johnson’s story is a stirring reflection of the broader struggle against racial injustice plaguing our society. His early life was shaped by the tumultuous context of Chicago’s segregation.

Despite this backdrop, Dr. Johnson excelled academically and was part of the first freshman class to experience integrated learning at Von Steuben Science Center College Prep High School on the North Side of Chicago. As he navigated the complexities of his profession, he became ensnared in a web of deceit and discrimination, illustrating the dangerous intersections of race, power and the law.

Rising Star

Photo Provided

Dr. Johnson’s rise in the field of psychiatry was remarkable. Emerging as one of the few Black psychiatrists in the nation after his medical training, he embraced this title with pride and a profound sense of responsibility. He believed in the healing potential of his profession and aspired to bridge the gap between mental health services and underserved communities.

At institutions like Mount Sinai Hospital Medical Center, Jackson Park and Cook County Hospital, Dr. Johnson honed his expertise, dedicating himself to the most vulnerable populations in Chicago. His academic journey—spanning the University of Illinois at Chicago, Harvard University and Rush Medical College—highlighted his qualifications and resilience in the face of systemic challenges.

Eager to provide care in an overlooked area, Dr. Johnson opened his practice in Anderson.

Initially welcomed, he quickly gained a reputation as a compassionate healer. However, as his practice flourished, so did the undercurrents of resentment from those who could not accept a Black man in a position of authority. He began experiencing strange and unsettling events, particularly when someone entered his apartment without his consent.

“I had the weirdest damn feeling, and I couldn’t put my finger on it. I don’t know what it was. I never felt comfortable in that place,” Dr. Johnson said. “I would walk in that apartment from day one and couldn’t explain it. And you know, somebody told me what that was; they were coming into my house while I was gone, and my spirit was picking up on it when I’d return.”

Following a series of chaotic and unsettling incidents that felt eerily stalker-like, it was in this critical moment that the event poised to change everything began to unfold.

The Incident

One fateful night, Dr. Johnson drifted into an uneasy sleep in his living room.

Awakened by an unsettling sense of apprehension, he opened his eyes to see a looming silhouette filling his window. Panic surged through him, intensified by chilling warnings from Sheriff Vera, who had alerted him to a hit on his life—allegedly orchestrated by someone within the sheriff’s department. Alone and vulnerable, dressed only in his underwear, he felt paralyzed by fear.

“I had woken up several times that night because I had weird nightmares. During that time, I had nightmares I had never had in my entire life. It’s weird how the mind works. I’m laying up on my loveseat by my patio that night. In my dream, a white guy walked up to me with blue jeans on and walked up to me and put his arms around me and strangled me. This was in my dreams, prior to the incident happening. I woke up in a sweat. I looked around in my front room, then I drifted back to sleep ten minutes later,” he said.

“As I awakened, and my eyes acclimated to the dark, it cast the shadow. I could see a silhouette of a human. I said, ‘Wow.’ I could tell it was mostly likely a male. Everything that Vera told me was like a recorder going through my mind,” he said.

“I thought to myself, ‘This is it.’ I was helpless. I was in a pair of underwear. I didn’t think they would come to my home,” Dr. Johnson said. “When you get a sudden fright, you go through a phase of paralysis…I kept the lights out, as Vera said. Everything was off, and it was dark, and I’m sure he probably couldn’t see me.”

Recalling Vera’s advice to keep the lights off at night, he realized the darkness could be his ally. Grabbing his shotgun, he prepared to confront an unknown assailant. Breathless and tense, he understood that he was not merely defending his life; he was fighting against an oppressive specter of racial violence.

In a moment that would spiral into a legal nightmare, Dr. Johnson defended himself against the intruder, setting the stage for a trial that would challenge the very fabric of justice.

The Trial

The trial became a spectacle, revealing the depths of prejudice and systemic racism. Key moments laid bare police corruption as biased testimonies used to attack Dr. Johnson’s character. His defense attorney highlighted shocking instances of police misconduct, yet the prosecution relied on shaky evidence and manipulative narratives.

Dr. Johnson’s true dedication to his patients and community was systematically erased. The jury, influenced by pervasive racial stereotypes, delivered a guilty verdict.

The emotional weight of that moment hung heavy in the courtroom—a painful reminder of the harsh realities faced by many Black men in America.

Ultimately, Dr. Johnson would spend 18 long years in prison, a devastating and unjust consequence of a system that failed him.

Consequences and Reflection

The original Chicago Defender article on Dr. Van Johnson (Provided).

In the aftermath of Dr. Johnson’s conviction, the implications rippled through his community. Tragically, many of his friends and family turned their backs on him, believing the rumors that he had not defended himself but had instead murdered the husband of his mistress—a claim that was utterly false. Most publications failed to represent his story accurately; local newspapers ran daily front-page articles fueled by rumors, innuendos and leaked police information.

“I couldn’t believe they were saying I killed a white man over a white woman. I had never dated white women, only Black women,” Dr. Johnson said. “And people just believed it. This told me something about Black people. It told me that white people are the ultimate authority on Black life. That’s the way I saw it, and I said to myself, ‘This is deep.’ It broke my heart.”

However, a couple of voices stood out amidst the chaos: Henry Lock, the managing editor at The Chicago Defender at the time who took Dr. Johnson’s calls from prison and the late Dr. Conrad Worrill, an educator, author and civil rights activist from Chicago. Dr. Worrill penned a story for The Chicago Defender, titled “The Dr. Van Johnson Case,” published on August 1, 1990, which accurately conveyed Dr. Johnson’s side of the story when other publications did not.

“Throughout the years, African Americans have been present in this country, there have been countless times that they were unjustly charged and convicted by the white-dominated criminal justice system. Another such case appears to be emerging,” Worrill wrote. “On June 10, 1990, Dr. Van Johnson, who was living and practicing psychiatry in Anderson, Indiana, from all reports we have received, accidentally shot a white man, James Wagner, 44, who apparently was prowling around his property.”

Worrill laid bare Dr. Johnson’s predicament: “Anderson, Indiana is a small predominantly white town about 250 miles from Chicago. Dr. Johnson moved to Anderson to set up his practice in July of 1989. During the year that Dr. Johnson has lived and worked in Anderson, he reported to his family and friends in Chicago that there was strong resentment by the white community against him setting up his psychiatry practice in the town. He had been harassed on numerous occasions, and in fact, his life had been threatened, as well as his property.”

Worrill also depicted why this successful Black psychiatrist was hated in this community.

“Apparently, some of the white people in Anderson were upset because Dr. Johnson was treating white patients and had a white secretary. His practice seemed to be developing quite well, which caused even more resentment on the part of some whites in the town,” he wrote.

And according to Worrill, here’s what really occurred:

Dr. Johnson goes on to state that “when he opened his door, the weapon accidentally discharged and the apparent figure he had seen daring outside his window fell forward. Dr. Johnson explains he tried to identify the victim and attempted to save his life through resuscitation. When it was apparent he could not revive the man through resuscitation, Dr. Johnson called the police. The victim died on the scene.”

Another Chicago publication, The Burning Spear, provided a credible account entitled “African Doctor Railroaded,” which labeled the victim—or rather the assailant—a Klansman.

Yet, Dr. Johnson’s education, credentials and connections could not help him.

He was a heavily connected man in Chicago, with ties to influential figures in politics, culture, music, media and the medical industry.

Yet, his network could offer little protection against the tide of prejudice he faced in Anderson. The lack of support from those who once stood by him underscored the isolation he felt, amplifying the injustice of his situation.

However, Dr. Johnson did not let this injustice be his end.

Call to Action

Dr. Van Johnson (Photo Provided).

His resilience in the face of adversity highlights the urgent need for his story to be heard. It is essential for Americans of all backgrounds to understand the uncomfortable truths it reveals about systemic oppression and racial injustice.

We must honor Dr. Johnson by advocating for justice and supporting those fighting against inequality. His journey compels us to take action and ensures no one else suffers his fate. He stated, “The fight for justice is not just personal; it’s a fight for all of us.”

Let’s amplify his voice, promote accurate reporting, and unite in the struggle for racial equality. By doing so, we transform his narrative into a powerful catalyst for change, paving the way for a future where justice is accessible to all.

Writer Inez Woody with Dr. Van Johnson (Photo Provided).