This article was originally published on Word In Black.

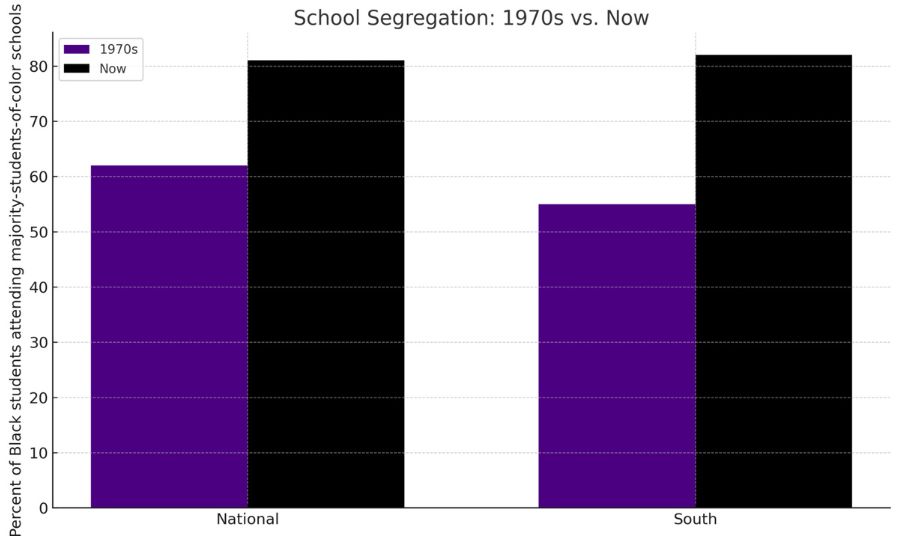

Decades after the watershed Brown v. Board of Education decision, multiple studies confirm that K–12 public schools across the country are more racially segregated today than they were in 1954, when the case was decided.

Just weeks before the 71st anniversary of that historic ruling, the U.S. Department of Justice quietly ended a long-standing federal school desegregation order in Louisiana — a case that had remained under court supervision since 1966.The news received little national attention, but experts warn it could mark the beginning of a bigger unraveling of the legal protections Brown made possible for Black students.

DOJ officials argue that schools in Plaquemines Parish, a district just south of New Orleans, had already been declared “unified,” and in compliance, for years. Still, civil rights advocates say the timing and political context of the decision — made as the Trump administration pledges to eliminate the Department of Education — signals a disturbing shift. One where the federal government has moved from decades of federal oversight meant to enforce Brown v. Board to actively dismantling those protections.

“The first thing Black folks wanted after slavery was education,” Raymond Pierce, President and CEO of the Southern Education Foundation, tells Word In Black. “Now the gains we made over the decades are in recession. This is a bad time for Black folks to not be educated to the maximum extent possible.”

Resegregation Is Already a Reality

Despite national claims of progress since Brown, the number of majority-minority public schools has actually increased. That retreat, fueled in part by white flight, contributed to deep racial inequities in access to quality education that decades of federal policy under different presidential administrations have failed to close.”

Even though Brown was handed down generations ago, more than 130 school districts nationwide are still under federal desegregation orders, according to the UCLA Civil Rights Project. But research shows that when those orders are lifted, Black students are likely to end up in highly segregated, under-resourced schools within just a few years.

“The first thing Black folks wanted after slavery was education. Now the gains we made over the decades are in recession.”

– Raymond Pierce, President And CEO of The Southern Education Foundation

“Almost every dimension of educational opportunity — including teacher qualifications, curriculum, experienced administrators, and access to AP courses — is linked to segregation by race and poverty,” says Dr. Gary Orfield, Co-Director of the UCLA Civil Rights Project.

That level of segregation continues to result in worse academic outcomes for Black students. A 2023 report from the Southern Education Foundation, “Miles to Go: The State of Black Education,” found that Black students are consistently behind in reading, math, science, and graduation rates compared to their white peers — a backslide from gains made in earlier decades when desegregation orders were more aggressively enforced.

Decades after the watershed Brown v. Board of Education decision, multiple studies confirm that K–12 public schools across the country are more racially segregated today than they were in 1954, when the case was decided.

“We’re not being prepared,” Pierce says. “Education innovation is transforming the world, and we’re not in the loop. Our education systems are not set up for us, and our communities are not healthy enough to close that gap.”

Less Oversight, More Barriers

In underfunded districts where desegregation mandates have lapsed, Black students are far more likely to be taught by inexperienced teachers, face larger class sizes, and have less access to advanced coursework. Without federal oversight, many schools will no longer be required to track — let alone correct — racial disparities in student access or outcomes.

Pierce says the DOJ’s Louisiana order doesn’t just raise alarms about the future; it reopens wounds from the past: “Those segregated schools were staffed by thousands of Black teachers and administrators,” he says. “They were pillars in our communities. But many lost their jobs during desegregation. That’s the part people forget.”

Orfield also adds that desegregation cases were more than symbolic — they were legal tools that forced education systems to address racial inequality. Now, he says, that burden falls back on Black families, who often lack the resources to file new complaints with the Education Department or challenge discriminatory school policies in court.

“Almost every dimension of educational opportunity is linked to segregation by race and poverty.”

– Dr. Gary Orfield, Co-Founder of The UCLA Civil Rights Project

The desegregation court orders “were designed and put in place to correct decades of state-sanctioned neglect,” he says. “Dropping them without real compliance means abandoning that responsibility.”

As the federal government under President Donald Trump looks to lift even more desegregation orders — without guaranteeing equity has been achieved — Pierce fears Black students could suffer a new round of setbacks, not unlike those their parents and grandparents endured.

“You can dismantle segregation without dismantling the very people who’ve held these communities together,” he says. “But that takes intention. That takes resources. And right now, we’re seeing neither.”

A Renewed Call to Action

Pierce says whether the courts move slowly — or not at all — Black families and communities don’t have the luxury to wait. He says they must fight for fair education now.

“We need to start attending school board meetings and asking the real questions,” he says. “Do we have enough math teachers? Do our kids have access to broadband? Are they even learning what they need to survive and thrive? That’s where the fight is now.”

He also encourages Black communities to lift up Black teachers, who have historically played a critical role in guiding and protecting Black students: “The Black teaching profession used to be the backbone of our communities,” Pierce says. “We need to bring that back.”

And adds that everyone has a role to play in correcting modern-day segregation.

“We can’t check out. This is about Jim Crow — and the children of the people who survived it,” Pierce says. “If we don’t fight for them, who will?”