This is Part Two of the Chicago Defender’s series Black and Unhoused: How Segregation Fueled a Homegrown Crisis, which is part of the “Healing Illinois” initiative.

Demetrius France, 55, is just 15 credits shy of earning his Associate’s degree.

“I started college in the early 1990s and studied electrical engineering and aviation at Florida Memorial University.”

When his heart led him to Chicago, he hoped to finish college, too. But life and a few challenges: marriage and separation, unemployment, and children delayed those goals. And now homelessness pushes that goal even further away.

Today, France is a resident of Inner Voice’s Systemizing Options and Services (SOS) – Joint Transitional-Rapid Rehousing Program on Chicago’s West Side.

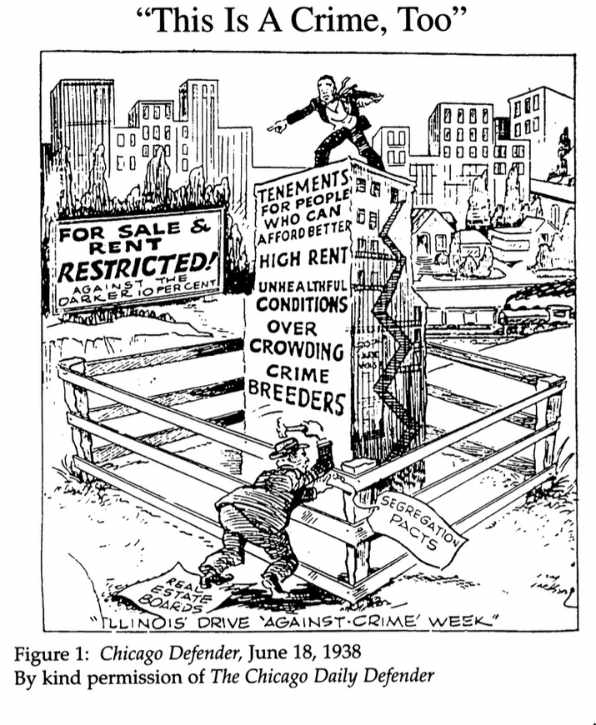

According to a 2021 Chicago Coalition for the Homeless-US Census analysis, 68,440 Chicagoans experienced homelessness, and 53% of them were Black. This staggering statistic mirrors a trend that dates back to the 1930s when the Chicago Sun-Times (then the Daily Times) reported that there were “50,000 homeless Negroes” living within the nine square miles of Bronzeville that confined the growing population of Blacks due to race-based restrictive covenants.

These racist, institutionalized barriers blocked access to communities with affordable quality housing that has endured for nearly a century, officials agree.

Moreover, despite the best efforts by local officials, advocates and other stakeholders, there does not appear to be a durable, sustainable solution to address the scarcity of affordable housing on the immediate horizon.

Therefore, a long and unbroken tradition spanning generations remains intact: Black people in Chicago lack access to safe, affordable housing.

Houselessness as a Racial Equity Issue

When Black Americans made their way to Chicago during the Great Migration, they planted roots in Bronzeville. By the 1940s, the neighborhood was one of the few places where Blacks could live, as 80% of Chicago’s population was under restrictive covenants.

Department of Family and Support Services Commissioner Brandie Knazze suggests that today’s Black homelessness issue is borne out of these covenants and the subsequent lack of investment that obliterated these communities once those housing restrictions were lifted.

As a result, Knazze notes, “Black Chicagoans are disproportionately at risk of becoming homeless, and that’s because of systematic racism and disinvestment of our communities.”

CCH Executive Director Douglas Schenkelberg is of the same belief, stating that Black homelessness in Chicago “is another example of the realities of structural racism.”

“We can list a long history of laws that have been in place that explicitly advantaged White folks over Black folks, and the disproportionate impact of homelessness on Black folks is a direct result of that.”

And while race-explicit laws like restrictive covenants are a relic, there’s still the undercurrent of racism and how housing decisions are made out of who has access to what, Schenkelberg said.

Helping to Right ‘Historical Wrongs’

To acknowledge and address those historical wrongs, Knazze’s office has made several strides to ensure that houseless Black Chicagoans receive equitable support services.

“In 2020, we received $35 million in CARES Act funding to support our rapid rehousing initiative where 74% of the 2,500 recipients were Black or African American. Since then, we’ve added $70 million from the City’s Corporate Fund and American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds to continue this effort into 2024.”

The rapid rehousing initiative ensured that individuals formerly living in shelters would relocate to facilities where they could have access to their own bedrooms and bathrooms.

DFSS has also made personnel shifts, including hiring a Director of Strategy, Equity, and Impact to ensure that the office “changes (s) the mindset of staff that interacts with nonprofits [who lead front-line work] to make sure that we’re not bringing our own biases to the table,” Knazze assets.

This shift has implications for how the unhoused receive support for such a personal life challenge.

France reflects on his experiences of bouncing from shelter to shelter before landing at Inner Voice because of the disregard he experienced from several shelter coordinators: “The people [at the other shelters], they had an attitude like, ‘You coming to us for help, we are not asking you for help.'”

So it is in this shift that Knazze’s office and others hope to be more responsive to the needs of the unhoused in general, especially people of color and returning residents like Vontarous McClendon.

“This Is A Crime, Too,” a Chicago Defender cartoon from 1938.

Black, Formerly Incarcerated and Homeless

The connection between homelessness and incarceration is inextricable.

A 2007 Urban Institute report highlights that over the last 42 years, the United States has seen an increase in both incarceration and homelessness. Furthermore, a 1999 Urban Institute national survey underscores that 54% of those who received homeless services were formerly incarcerated — a reality that remains prevalent today.

As such, the formerly incarcerated are nearly 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

But to be a person of color and formerly incarcerated, the likelihood of homelessness is even higher.

For instance, Black and Hispanic women who are returning from incarceration “experience unsheltered homelessness at significantly higher rates than White women.”

The same follows for formerly incarcerated Black men like McClendon, who also experience unsheltered homelessness at significantly higher rates than White and Hispanic men.

The 44-year-old McClendon, a participant in Inner Voice’s SOS program, has lived in Chicago for almost 20 years since graduating high school.

“After high school, I thought about going to college but ended up doing other things that I shouldn’t have done and missed my ticket to college. I sold drugs and spent some time in jail. After the last time, I decided I needed a change.”

The DFSS has significantly invested in supporting formerly incarcerated citizens’ return to society.

Commissioner Knazze explains how her office has prioritized helping returning citizens sustain a new path forward after incarceration.

“We want to address re-entry and make sure we’re reducing barriers for individuals who are returning from incarceration. For a lot of people, when they return, they may not have a place to go. And they’re [at a ] higher risk to become homeless and return to the life that they were in.

So, [in December 2023] we used some of our ARPA dollars to create a fifth re-entry center on the Westside.”

The department and private donors have invested in their flexible housing pool to house 1,000 people, and 70% of those were Black.

Flexible housing is a cross functional partnership across various city departments, Cook County Health and CHA to provide supportive housing for those in need, in lieu of them relying on jails, emergency rooms or shelters to meet their needs.

Despite the city’s comprehensive investment to stem the legacy of unhoused Black Chicagoans like McClendon, there is still a significant need for more housing.

In light of the crisis that has brought nearly 40,000 migrants to Chicago in less than two years, the government — county, city and state — has spent nearly $2 billion to help new arrivals settle into Chicago. Some funding includes federal pandemic funding intended to support individuals whose issues predate the migrant crisis.

For many Black Chicagoans, the unprecedented price tag leaves many wondering about those who have been seeking support long before the first arrival. Before McClendon arrived at Inner Voice, he lived in a motel for eight years.

It was until he got into a car accident that prohibited him from working that he had no recourse but to turn to the streets for shelter.

“I slept outside for about four or five months: in the back of buildings, behind a tree. After my accident, I was sleeping outside of a gas station,” he said.

McClendon feels his experiences are overlooked in light of the migrant investment. “We’re already homeless here. What happened to the people that were here already? Why not help them, you know?”

Why Bring Chicago Home Didn’t Make It Home

Before the March 19 primary, members and supporters of The Chicago Coalition for the Homeless rally for Bring Chicago Home (Photo, Facebook).

Bring Chicago Home was a ballot referendum to institute a new real estate transfer tax to properties over $1 million.

The fund would provide an estimated annual $100 million in sustainable revenue to fund affordable housing solutions to address chronic homelessness in Chicago.

The BCH coalition suggested that the measure is a continuation of Black Chicago’s quest for Civil Rights and fair housing and investment in the Black community, considering that the majority of Chicagoans experiencing homelessness are Black.

However, critics stated that the proposal lacked a sound plan.

Chicago voters had the opportunity to pass this measure during the March 2024 primary, but it failed by 20,000 votes. Christopher Berry, a Professor at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, offers perspective on those reasons.

“I don’t think they did a good job of explaining how this money was going to be used.”

The resolution sought to change the city’s portion of the real estate transaction tax but did not articulate what it would be used for. Only the ballot referendum question stated that “the revenue from the increase…is to be used for the purpose of addressing homelessness, including providing permanent affordable housing and the services necessary to obtain and maintain permanent housing in the City of Chicago.”

Mayor Brandon Johnson considered the Bring Chicago Home referendum as one of the signature initiatives of his administration. His committee provided $100,000 to get this passed.

Some might argue that BCH was a progressive tax in that it would tax individuals in higher income brackets. Berry suggests that those behind the referendum were motivated by this in principle: “We just want to tax the rich. We just believe [that] in principle that that’s a good thing to do.”

Generally, this was supported in 2020 when 71% of Chicago voters supported the progressive income tax in 2020.

However, according to Berry, given the current economy, voters were turned off by this logic.

“I don’t think most voters were buying that. In the abstract, that’s not a good thing to do, right? It could be a great thing to do if you tell me for what purpose and [what you’ll] do with the money.”

What’s more, it’s the crisis surrounding the Loop.

As of April 2024, there is a 25% office vacancy in Chicago’s downtown with very little demand, as reported by Crain’s.

Berry affirms, “We’re in a different moment now economically in the city than we were back when the Fair Tax was proposed. The real estate crisis [is] just as a broader marker of the crisis surrounding the future of downtown. [And] that’s for real. I think most Chicagoans know it, and they can see it, and we all really need to be worried about it because it is the economic engine of the region.”

“I think voters see that, and they are worried about how we are going to make an economic comeback if we also just start raising taxes at this moment.”

Black People Still in Waiting

Despite the apparent need and nearly century-old burden to house Black Chicagoans, the city is still slow to mirror immediate changes that would rapidly change thousands of Black lives as they have for the over 35,000 migrants that have arrived in Chicago.

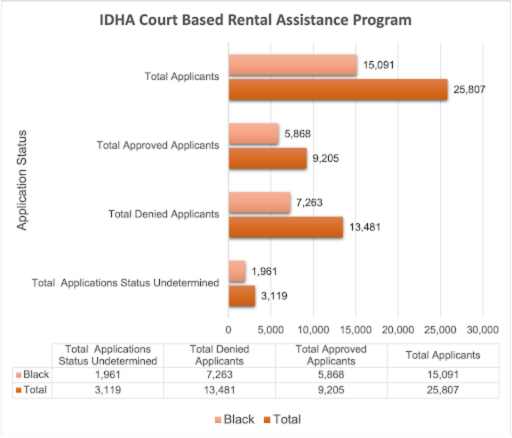

The need for housing security impacts not only those experiencing homelessness but also those who face housing insecurity due to being cost-burdened. Cost-burdened housing is considered paying more than 30% of monthly income. When the Illinois Housing Development Authority (IDHA) began accepting applications for its Court-Based Rental Assistance Program, over 15,000 of the nearly 26,000 statewide applicants were Black. Out of 25,807 applicants, the program would provide rental support to roughly 9,200 applicants who were approved and offered support.

Of those applicants, 15,091 (58%) were Black, and 5,868 (63%) of approved applications were Black. Of those who were denied support, 7,263 (53%) were Black. It means thousands of Black Chicagoans struggle to keep up with their rent, pushing them to the brink of homelessness.

Chart: Nicole Jeanine Johnson/Chicago Defender NewsSource: Illinois Housing Development Authority Created with Excel

Three years after receiving $1.887 billion in COVID-19 relief funds, the city has yet to spend down the $1.227 billion appropriated to advance social and community support, provide targeted economic relief and develop neighborhoods.

Of that, $157.4 million would go towards affordable housing, $157 million towards assisting families, and $117 million towards homelessness support services. They anticipated that more than 3,000 vulnerable and homeless residents would be connected to resources and more than 4,000 housing units would be created or upgraded to be affordable. These estimates predate the first arrival of migrants in August 2022.

Moreover, in late 2023, the Johnson administration leveraged $95 million of those dollars to address a shortfall in migrant relief.

Demetrius France, resident at Inner Voice, expresses confusion about the use of funding for new arrivals despite the longstanding issue of homelessness.

“I don’t understand it. How can these people come and get assistance when you’ve been here in America, and [we] have our own homeless situation? How can the immigrants get the billions of dollars that they’ve received in assistance, and you, as an African American, can’t get it?”

When Mayor Brandon Johnson was asked about addressing this issue that Chicagoans have been dealing with for decades, he pointed to the $1.25 billion bond that the City Council passed on April 19. He sees this bond as a revenue source to support the city’s existing needs.

“I’m confident that the people of Chicago will have their voices heard through the City Council. Now I’ve put forth my vision that we need these resources right away for housing, commercial economic development, homeownership, etc.”

Johnson sees the bond as “a down payment towards larger investment” that could ultimately put more money in the pockets of Chicagoans, like “sustainable guaranteed income.”

But directly addressing the needs of Black Chicagoans will take time.

VIDEO STORY: Black and Unhoused in Chicago: How Housing Segregation Fueled a Homegrown Crisis

This article is part of the Segregation Reporting Project, made possible by a grant from Healing Illinois, an initiative of the Illinois Department of Human Services and the Field Foundation of Illinois that seeks to advance racial healing through storytelling and community collaborations.

The project is inspired by “Shame of Chicago, Shame of a Nation,” a new documentary that addresses the untold legacy of Chicago’s systemic segregation.

Managed by Public Narrative, this endeavor enlisted five local media outlets to produce impactful news coverage on segregation in Chicago while maintaining editorial independence.