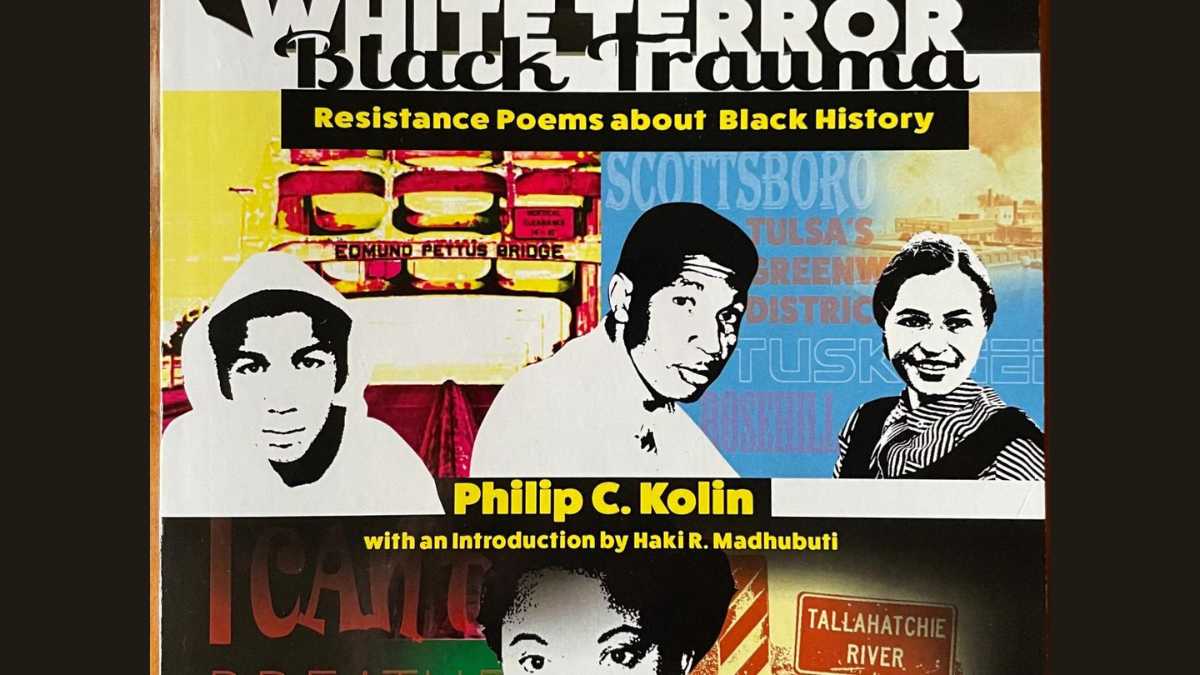

[perfectpullquote align=”left” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“White Terror, Black Trauma: Resistance Poems about Black History” by Philip C. Kolin / Third World Press, 2023 [/perfectpullquote]

Review by By Rev. Dr. Brenda Eatman Aghahowa

During a season of U.S. national life when many conservatives are seeking to ban the comprehensive, full-throated teaching of African American history comes another searing collection of poetry by Philip C. Kolin, Distinguished Professor Emerita of English at the University of Southern Mississippi.

It is a must-read for anyone who is not afraid to look America’s original sin of slavery and its ongoing racism squarely in the face, and who wants to grow stronger and wiser by Kolin’s prolonged and profound stare. Ostensibly a literary work, Kolin’s, “White Terror, Black Trauma: Resistance Poems about Black History,” serves as both a primer in American Black history and a tribute honoring social justice icons and martyrs.

The book is dedicated to Mamie Till, mother of young Emmett Till, whose 1955 murder helped to ignite the Civil Rights Movement.

Introduced by Black Arts Movement luminary Haki Madhubuti (Don L. Lee), the 61 resistance pieces pack a punch poetically and emotionally. Each either lifts up an important individual or individuals and/or illuminates an important theme. A headnote provides the context for each poem. Often chilling in their stark imagery and powerful language, they also inspire hope and pride.

All the familiar names a reader might expect are there as Kolin explores the sociopolitical circumstances and the topography of Black trauma, harassment and brutality experienced by Blacks here in what Maya Angelou has called these yet-to-be United States.

Trayvon, Rosa, Martin, Malcolm, Medgar, Harriet, Denmark, Ruby, James, Breonna, Bessie, Billie, Ahmaud, Sojourner, the Scottsboro Boys, and so many others find reverence and/or remembrance in these pages.

The reader often is struck by the irony of how the killings of many of these persons only served to amplify their voices, fuel protests and secure their legacies. Through Kolin’s brilliant creativity, we are reminded that books, films, recordings, statues, museums, monuments and movements continue to honor them.

Those of us who pride ourselves on extensive knowledge of Black history are humbled and brought low when, while savoring these writings, we discover lesser-known figures, such as Tituba of the Salem witch trials (“Tibuba’s Forced Silence,” 2), and events of importance to Black women, such as the July 4, 1970 women’s rights demonstration at the Statue of Liberty (“The Lady in the Harbor,” 51). “How did I miss these things?” this reader sometimes had to ask herself.

While making skillful use of alliteration, word play and enjambment, Kolin takes us to parks and rivers and city streets and Ebbets Field and a Memphis hotel balcony and churches and court rooms and slave ships and a night club and Tuskegee science labs and lunch counters and a kitchen table (where a hard-working mother’s children of poverty must eat stale bread with mold on it) and pools and a bridge and a prison farm and schools and polling places, and so many other venues.

We are made angry by the ‘voting rites’ that forced us to guess the number of jellybeans in a jar (“Voting Rites in America,” 67) and infuriated by the environmental racism that forced Flint, Michigan’s mostly Black residents to drink and use water that gave them rashes and diseases, and that stunted children’s development (“Black America’s Sick Waters,” 59).

Faucets in Flint, Michigan drip, drip, drip

junk cars, rusted pipes, paint cans, and tossed

refrigerators as lead seeps into Black babies’ brains. (59)

These poems are not for the faint of heart, nor are they for those who are afraid they will make themselves or their children ‘uncomfortable’ by reading them. For we are horrified by haunting images of lynchings and of maimed bodies at the bottom of the Tallahatchie River and other waterways.

Kolin pays homage to famed blues women Bessie Smith, Victoria Spivey, and Billie Holiday, referencing the words to the latter’s song, “Strange Fruit,” in the piece, “The Three Ladies Blues.”

His cadence and rhythmic flow mirror that of Billie’s singular song styling.

They are in Billie’s voice, tears

for all the lost Black futures hanging

on lynching tree – bodies with bloody leaves,

twisted flesh for crows to pluck and plunder.

Coffins lined up like cotton rows.

Through allusion to this protest music, we are reminded that the blues women paved the way for other socially conscious songs. These include Marvin Gaye’s “Make Me Wanna Holler” and “What’s Going On?”, James Brown’s, “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give me Nothing (Open Up the Door, I’ll Get it Myself),” and Lauryn Hill’s, “Black Rage.”

In “Tallahatchie Tears” (28), Kolin, who calls himself a cradle Catholic, and whose poetry and lyrics have been published in various Christian magazines and sung in churches, makes one of his many skillful uses of religious imagery and themes.

The Tallahatchie is filled with Black moans

of men and boys, throats slit or hung, thrown

into the river of perdition, this river of rocks

shackling them in muddy graves…

Men with defiled souls have fished here

snagging shadows and ragged raiment,

remnants of church choirs, pickers’ bones,

faces full of fright, heads without eyes.

Tallahathchie, you are the apostasy of baptism.

George Floyd’s killing is described in, “Golgotha Outside Cups,” and calls to mind Christ’s crucifixion on Golgotha’s hill.

Chauvin’s iron knee, like the carcan at the pillory,

ringed George’s neck.

A man of sorrows, defiled, his face a history

of lynching, except by a new method, prone torture.

Golgotha traded places with the intersection of Chicago and 38th.

The headnote for the poem, “Bombingham” (41), which also powerfully invokes Christian themes, offers the names of the four little girls who were killed in a church bombing in Birmingham on Sept. 15, 1963: Addie Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Carole Denise McNair.”

With stunning use of personification Kolin writes,

So horrific was the hate that blew

the old 16th Street Baptist Church apart

that September day. Four girls glad in their best

Sunday graces, trampled, their lives dashed

to stone by KKK ruthlessness. The church walls wailed.

And God’s voice could be heard above the terror

in that only surviving stained-glass window

where Jesus is calling his children to him.

The girls heard and came, their smiles

preserved for history’s tears.

Similarities between the persecutions of Blacks and Jews also appear in this work, references being made to the Holocaust and 1938’s Kristallnacht seige (sometimes referred to as the Night of Broken Glass). Kolin writes in, “Kristallnacht in Tulsa” (20),

40 square blocks of shops, banks, schools,

hospitals, churches, museums, a theatre named

Dreamland, the capital of Black Wall Street

that never suffered a crash before

until deputized vandals for over 18 smashing hours

into the night blitzkrieged this Black paradise…

The jewels of Black culture and the ingenuity of Blacks that are displayed in Kolin’s pieces are too many to enumerate in a brief review of this kind.

One is reminded, for instance, while reading, “A Black Woman Called Moses” (7), of the coded messages contained in spirituals that alerted slaves that Harriet Tubman was in town. Kolin’s strong storytelling ability is evident here as he indicates that on this night, Harriet would be meeting and leading her Underground Railroad passengers along the riverbank during their journey to freedom, this so that slave owners’ dogs could not pick up their scents.

Still, she never lost a passenger or any

who wanted to turn back, her pistol

a true compass stopping them, her voice

sometimes a song.

Wade Across the River Jordan, code…

Depictions of dark episodes of Black history in which Blacks lost our names, dignity, and lives in horrific ways are intermingled with warm words of tribute and triumph that hearten. The wonderful cadence of “Ain’t I A Woman” (14) delights the reader as Kolin writes of minister Sojourner Truth, the former slave Isabella Baumfree,

Across the centuries her adopted name

gave women a geography to selfdom.

Women in bell shaped skirts and broad brimmed

straw hats carried her words on posters to the polls.

The poem, “Soley Because He Was a Negro” (35), calls to mind the Supreme Court battle of James Meredith, who integrated the University of Mississippi (nicknamed Ole Miss). He had to be escorted to class “flanked by 31,000 registrars in khaki protecting him against rioters who had a diploma in hate mongering.” Meredith eventually earned his degree from the school and Kolin reports,

Some twenty years later, Meredith received

a letter from Ole Miss awarding him

the Distinguished Alumni Award

for his contributions to Ole Miss and

the State of Mississippi.

He did not need Border and Customs agents

guarding him when he opened the letter.

About the latest federal holiday honoring Blacks, Kolin pens these words in the poem, “Juneteenth” (11).

A Black day of independence.

A new African American day

of the month carved into calendars.

White time had to make room

for the jubilation of freedom.

This collection of poetry, one that features not only masterful poetic artistry but also extensive research, should be on every home bookshelf and in every library where serious readers excitedly tread. Kolin has presented an invaluable gift to the world.

Brenda Eatman Aghahowa is a Chicago State University Professor Emerita of English, an editorial consultant, and a minister in the United Church of Christ. The Cleveland native has more than 40 years’ experience as a print journalist, public relations account executive, and English educator. She has published and presented nationally and internationally on Black language justice, retention of Black college students, and Black worship. Her books include, Grace Under Fire: Barbara Jordan’s Rhetoric of Watergate, Patriotism, and Equality (Third World Press, 2010), and Praising in Black and White: Unity and Diversity in Christian Worship (United Church Press, 1996). baghahow@csu.edu