“Lapeace, man, I didn’t know you was Muslim…”

“I ain’t,” answered Lapeace. “I’m a gangsta.”

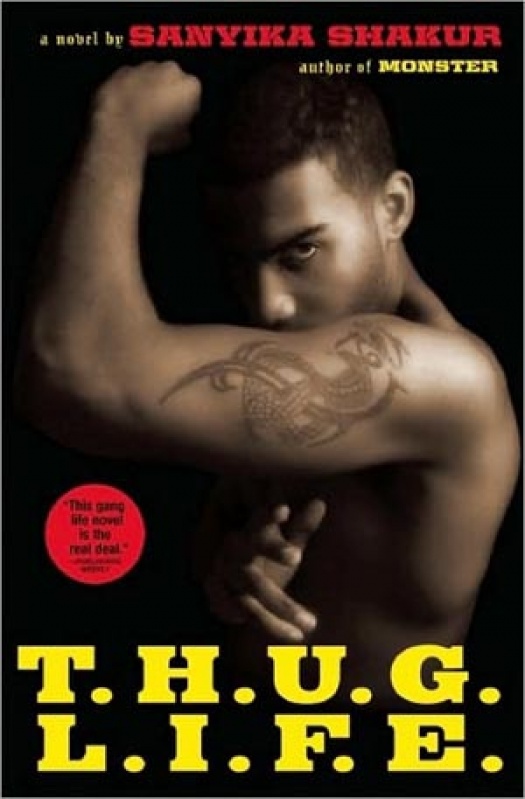

This exchange occurs in Sanyika Shakur’s latest novel, T.H.U.G L.I.F.E., after the the boo

“Lapeace, man, I didn’t know you was Muslim…” “I ain’t,” answered Lapeace. “I’m a gangsta.” This exchange occurs in Sanyika Shakur’s latest novel, T.H.U.G L.I.F.E., after the the book’s central character, Lapeace Shakur, the leader of South Central Los Angeles’ Eight Tray Crips gang, greets his Muslim lawyer with a traditional salutation, to the confusion of Maniac, a young gangbanger.

This seemingly insignificant exchange provides much insight into Shakur’s debut novel. The characters of T.H.U.G. L.I.F.E. worship gang banging as if it were a religion. They revel in the thug lifestyle, which usually involves sex, lavish materialism, drugs and heartless murder.

And even though Shakur proclaims the book to be a novel about “one man’s attempt to free himself” from gang life, by the end of the novel it seems clear that Lapeace will no sooner be ex-communicated than the Pope.

T.H.U.G. L.I.F.E. takes place during the mid-1990s. It follows Lapeace as the police search for him due to his involvement in the Crenshaw Massacre, an explosion of violence that led to the death of eight innocent people. As the novel proceeds, Shakur introduces readers to a vast cast of characters including Anyhow, Lapeace’s nemesis; Tashima, his girlfriend and CEO of a rap record label; John Sweeney, a corrupt Los Angeles Police Department detective; and various thugs and gangbangers.

While a young gangster may find T.H.U.G. L.I.F.E. to be a riveting tale, expounding on the truth of life on the streets, the average civic-minded citizen, whether Black or white, may have a hard time empathizing with Lapeace or being drawn into the gang world.

Any novel with such a harsh setting as this one needs to be vivid in order to seduce the reader. T.H.U.G. L.I.F.E. is like being at the beach and looking at the ocean from the sand, instead of diving head first into the water. Readers understand what is going on, but there is a disconnect. This is primarily due to a heavy authorial voice, which tells of violence rather than illustrating it.

While Lapeace, like the rest of the novel, does have three-dimensional moments, much of the time he is little more than flat. Lapeace has no qualities redeeming or convincing enough to garner him the title of anti-hero. Additionally, John Sweeney, who is admittedly no angel, is not crooked enough for readers to detest him, which they should.

The plot is complex, but it ambles along. The climax is unidentifiable, which makes the ending dissatisfying. A novel attempting to bring readers face to face with a raw gang-infested universe should have a fast pace that keeps the audience interested.

Nevertheless, T.H.U.G. L.I.F.E. deftly weaves together the extensive and complex histories of its characters with their present struggles. It also moves between the lives and thoughts of a plethora of characters without being boring or confusing.

Additionally, the novel uses slang to its advantage. It is always both authentic and appropriate, fitting of an author writing from his jail cell.