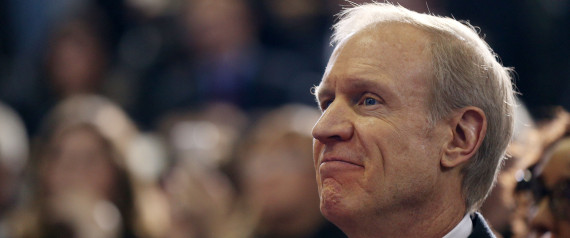

The billionaire Republican Governor of Illinois, Bruce Rauner, injected himself into ceremonies in Chicago last week presided over by the city’s Democratic mayor and the nation’s Democratic president.

Rauner insisted on attending because he wrongheadedly thought the Democrats were honoring his idol, kingpin George Pullman, the guy who invented the luxury railroad sleeper car, oppressed his workers and suppressed their union.

Rauner, and other kowtow-to-the-rich Republican governors, adhere to the Pullman philosophy that rich people are better than everyone else and that gives them the right to control the lives of everyone else. They don’t comprehend the dreams and desires of the middle class and working poor. So Rauner couldn’t conceive that the ceremony in Chicago’s South Side neighborhood named Pullman by Pullman for his personal self-aggrandizement was not about placing the mogul on a pedestal but really about recognizing the people who ultimately prevailed despite his exploitation.

At ceremonies designating the Pullman Historic District as a national monument, President Obama’s speech served as both a rebuke and history lesson for Rauner. The president told the tale of Pullman from the workers’ point of view.

Pullman constructed his first sleeper car three years after the Civil War ended and nine years later employed his first black porters for an expanded service. These black men and women were hired at low wages to work long hours to wait on wealthy white customers hand and foot. This was a Southern plantation travelling America on rails.

Porters, who had to pay for their own uniforms and equipment such as shoe shine boxes, depended on tips for much of their income. As a result, most kept silent as white passengers referred to them all by Pullman’s first name, “George.” This demeaning treatment inspired the 2002 Robert Townsend film 10,000 Black Men Named George.

The community Pullman built around his factory was a company town in all the worst ways. Pullman owned everything, the homes, the hospital, the shops, the hotel named for his daughter Florence, and, of course, the source of all income – the jobs.

Pullman believed he should decide what was best for all the residents. The town contained no taverns because he felt residents were better off without alcohol. He refused to allow workers to own their homes because he feared “the risk of seeing families settle who are not sufficiently accustomed to the habits I wish to develop in the inhabitants of Pullman City.”

During the recession of 1893 and 1894, Pullman slashed wages for workers, but not his own pay. He refused to ease rents and grocery costs, which would have reduced his profits, even as his workers and their children suffered. His row house inhabitants, barely surviving on soup kitchen handouts from Chicago charities, sent a delegation to negotiate with him. He wouldn’t relent, contending, as if he were a benevolent parent and not a insensitive tyrant, that they were “all his children.”

Not willing to subsist as helpless inhabitants of a rich man’s dollhouse, the community’s workers, who believed in America’s promise of self-determination, organized a strike. It eventually spread across the country as the porters joined in. Pullman got the President to send in federal troops who fixed bayonets on the populace and killed more than 30 workers.

The workers returned to their jobs, but they’d experienced the power of collective action. And that couldn’t be repressed. The workers cheered in 1898 when the state Supreme Court ordered the company town sold. It would take decades longer, but the workers eventually secured their goal of collective action on the job.

In 1925, the porters established a labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and chose civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph to lead it. At that meeting, Randolph explained why workers’ concerted action was essential: “What this is about is making you master of your economic fate.”

Pullman refused to recognize the union and tried to squelch it, firing as many members of the brotherhood as his spies could find. It took the workers 12 years, but finally after passage of the National Labor Relations Act, which provided a clear legal path to unionization, Pullman was forced to acknowledge and negotiate with the brotherhood.

Standing in the Pullman Historic District Thursday, President Obama said, “So this site is at the heart of what would become America’s labor movement — and as a consequence, at the heart of what would become America’s middle class.”

“As Americans we believe workers’ rights are civil rights. That dignity and opportunity aren’t just gifts to be handed down by a generous government or by a generous employer; they are rights given by God, as undeniable and worth protecting as the Grand Canyon or the Great Smoky Mountains.” President Obama said.

That, however, is not what Republicans like Bruce Rauner believe. They think, just as Pullman did, that workers’ rights should be circumvented, slighted and squashed for the benefit of the rich.

For more, go here.